The following is an edited transcript of a talk by Bilahari Kausikan, Ambassador-at-Large at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs in Singapore. It was delivered on 11 October 2017 at our monthly Singapore Platform for East-West Dialogue.

THE RELEVANCE OF SINGAPORE ON THE WORLD STAGE

I’m going to take some liberties with the topic. I’m not going to talk about the role of small states between East and West, but I’m going to talk about small states. I’m going to talk about why small states should not behave like small states—not if they want to remain states anyway. Now if you are a small city-state, which historically does not have a very good record of surviving, you have to start from a very stark and simple premise—you are intrinsically irrelevant. You perform no irreplaceable function in the international system. If you disappear from the face of the Earth, by this, I mean disappear as a sovereign and an independent entity, you will not make a whit of difference to anything.

After all, Singapore has, as a sovereign and independent entity, only existed for 52 years. That’s just a blink of an eye in the long sweep of history.

Now, what do we mean by small? I mean physically small. This is essentially one city and, in some context, not a very large city. In a Chinese context, you are a second-tier city, about five to six million people. Now, of course we are not going to disappear, but your sovereignty and independence can be severely compromised. And that is actually the case of most small states today. There are about 196 sovereign states, and 193 members of the UN. Most of them have a seat at the UN, a vote at the UN, a flag, a national anthem, but that’s about it. Their autonomy and their ability to carve their own destiny is, more often than not, severely compromised. Now, I said physically small. By some other matrixes, we are not so small. As a port, a sort of logistics centre, a financial centre, or a trading hub, we are not that small. But physical size does matter.

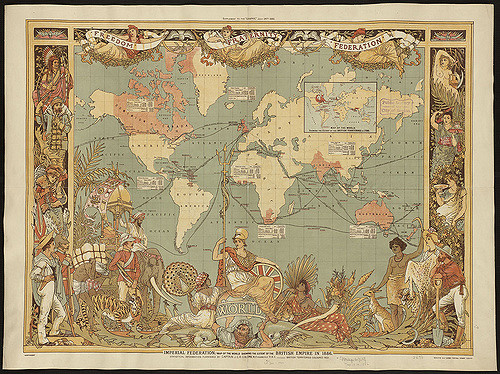

Why do I say that? Well, let’s take your role as a logistics hub and trading centre. We have performed that role, according to some accounts, since the 14th century. We have certainly performed that role as a British colony, and as part of Malaysia. Of course, the manner in which we perform the role has evolved, but it’s essentially the same role. So you don’t have to be sovereign and independent to do these things. You cannot take your relevance as a sovereign and independent country for granted.

Relevance for a small country and a small state is an artefact. That means something created and maintained by human endeavour. How do you create relevance? Relevance is a contextual concept. What makes you relevant today may be quite irrelevant in a week, in a month, in a year, or in a decade. What makes you relevant vis-à-vis country A, may be quite irrelevant vis-à-vis country B. What makes you relevant on issue X vis-à-vis country A, may be irrelevant vis-à-vis issue Y. For the purposes of this talk, I’m not going into the details of that, but you can ask me questions about that later.

That said, the bedrock of relevance is success. Before I retired from the foreign service, I used to tell our junior officers that if Singapore’s foreign policy had any success, it is not because—or when I’m in my kinder moments, I say “not only because”—of their good looks, their natural charm, and the brilliance of their intellect. It’s because Singapore is a successful country, and you represent a successful country. Therefore, what you say is taken with some seriousness and some credibility. If you serve in the UN, as I have, you will find many individual diplomats from many countries who are absolutely brilliant, but they are not being taken seriously. Why? Well, it’s simply because they are representing countries that are not taken seriously.

A SUCCESSFUL COUNTRY

Photo: Zehpylwer0 / Pixabay

What do you mean by a successful country? Here, I have to be very crass. Success, first of all, has to be measured in economic terms. If you are a basket case or a barren rock, nobody will take you seriously. You cannot be successful by any other criteria. Of course, that is the foundation, but that is not the end of it. Economic success gives you options that are not available to countries that, to put it crudely, do not have the cold hard cash in order to create options. Now, I’m not going to go into how to be economically successful. There are many pathways, and it is also in a state of constant change. But one thing is constant: even as you adapt to various changing circumstances to keep yourself successful, and adaptability is one criterion, you cannot be just ordinarily successful. You have to be extraordinarily successful. You can’t be successful as, let’s say, countries around you because every country around you is bigger than you. Brunei, is smaller in population, but is well-endowed with natural resources; oil and gas. Everybody else has natural resources. Therefore, even if you are as successful as everybody around you, why should they take you seriously? You don’t have any natural resources, and they might as well deal with a country larger than you.

Hence, you have to be exceptional. You have to be extraordinary. It doesn’t always make you loved, by the way, but that is the existential condition of being Singaporean. To survive and prosper, you have to be exceptional; in being exceptional, it sometimes creates resentment. You just have to deal with it and manage it. It follows, therefore, that you cannot take the advice of my former colleague, who advocated in a rather stupid article that small countries should behave like small countries. If Singapore had behaved like a small country in 1965, we wouldn’t be sitting here talking to each other, or we would be talking in a different language. At least it wouldn’t be me addressing you all, because I am not a bumiputra.

Now, that does not mean we should not be aware of the constraints of being small. Of course, you should be aware of the constraints of being small, but you should not allow yourself to be limited by those constraints. You should not allow your ambition to be bounded by your mere size because that is precisely what when we had independence thrusted upon us. Don’t forget that Singapore is quite unique. We never sought independence, we had it thrusted upon us. And, in fact, the late Mr Lee Kuan Yew is on record as saying small island states are a political joke. That’s why he sought independence within Malaysia. It didn’t work out, and we had to make it work. If at that moment of anguish, when we were thrown out on the perilous seas of independence, we behaved like a small country, we won’t be speaking here because that is precisely what the Malaysians wanted us to behave like. They had three powerful instruments. I won’t go into details, but the first instrument was the armed forces. During the crucial years of 1965-1969, we do not have an armed force worth talking about. Second, the economy. Singapore was still largely an entrepôt, whose hinterland was Malaysia and Indonesia, and both were out to replace us in that role. The third instrument was water. Essentially, the assumption was these three things would either bring us crawling back or keep us as a small country tamely to heel. The story of Singapore since 1965 is how we overcame those challenges by being exceptional.

Now, one element of Singapore’s exceptionalism is the organising principle of Singapore, which is multi-racial equality and multi-racial meritocracy. I’m not saying that we do it perfectly. In fact, we are far from perfect. But there is no perfection to be found outside heaven, if there is a heaven. I don’t quite believe there is a heaven, so there’s no perfection to be found. But even if you believe in heaven, at least the Christian heaven, there is also no equality, there is hierarchy; there is God, there are angels of various kinds etc. And if you look around Singapore, as imperfect as we are in implementing the organising principle, it is nonetheless unique and exceptional. Look around Singapore, not just in Southeast Asia, but from Northeast Asia to South Asia. Most countries are organised whether explicitly—in the case of Malaysia, where the principle of Malay dominance is enshrined in the constitution—or implicitly. It’s bumiputra over non-bumiputra; it is ethnic Thai Buddhist over Muslim Rohingya; it is Sinhalese Buddhist over Tamil; it is Han over non-Han. Even in a very liberal democracy like Japan, it is ethnic Japanese over Japanese-Koreans or Ainu; it is Hindu over non-Hindu; it is Buddhist over non-Buddhist; there is no end. You just think about what’s around us.

Even beyond that, in Western liberal democracies, there is a reassertion of hierarchy; it should be white Christian first. That is the meaning of the Trump phenomenon; that is the meaning of Brexit; that is the meaning of these right-wing movements that have arisen on continental Europe. They don’t always say it so explicitly, but when they are anti-immigration, for example, that’s what they mean. And this foundation which makes us unique is under pressure. It’s under greater pressure today than it ever was before because part of the backlash against globalisation is a cultural backlash. It is the assertion of identities of various kinds as superior over identities of other kinds. Now, there are many such assertions. There is the assertion of an Arabised form of Islam as more authentic than other forms; and there’s an assertion of various kinds of evangelical Christianity as more authentic than other kinds.

Similar ideas have crept into Singapore such as radical Hinduism and radical Buddhism. If you think about the fundamental tenets of these religions, it’s an oxymoron, but it exists. Even in a secular way, you have the assertions of different kinds of political identity as more authentic to the exclusion of other kinds. What has that got to do with us? We are exposed to these things, and you can’t insulate yourself from these things. You can perhaps mitigate those things, but you can’t insulate yourself, because the cost of shutting yourself off is to try and become North Korea, and you know where that leads to.

Singapore is not just a small country, it is also unique in another way. Singapore is the only ethnic Chinese majority country outside greater China, by which I mean the People’s Republic of China, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Macau. That poses particular challenges, particularly with relations with China.

THREE TRACKS TO CHINA’S FOREIGN POLICY

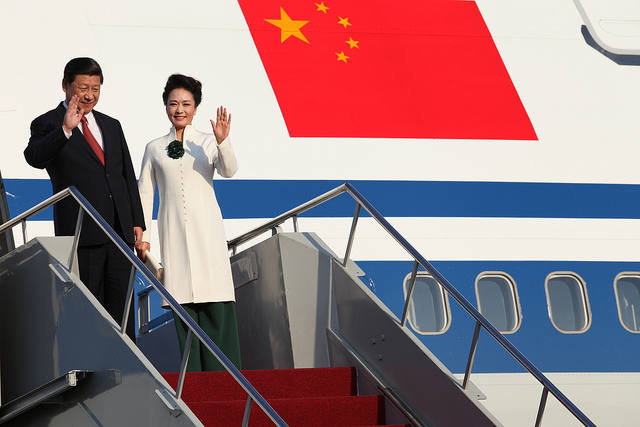

President Xi Jinping and his wife, Peng Liyuan. Photo: APEC 2013 / Flickr

Chinese foreign policy is unique in one way; it does not conduct international relations on only one track. It conducts international relations on three tracks. Of course, all countries, including ourselves, have more than one track of foreign policy. But China does it more insistently, much more systematically, and with a greater institutional apparatus devoted to the different tracks than any other country I know. What are these three tracks? The first is, of course, the normal track of state-to-state relations. These sometimes fluctuate up and down, and that’s quite normal. There is no substantive relationship of any country anywhere that is a smooth trajectory. I mean we have a smooth relationship with at least one country I know of. Guess which country that is? It is Botswana. You know why? Because there’s no substantive relationship with Botswana. Once you have a substantive relationship with a country, it’s bound to fluctuate. In other words, smooth trajectory in a relationship means that the relationship is, by and large, irrelevant. The state-to-state relationship we have with China is, by and large, not bad. There are ups and downs of course, but it’s still not bad, even quite good.

But that’s not the only track. China is not just a state, it is also what I would call a Leninist state. I don’t use the term “Communist” because I don’t think there’s anybody in China that seriously believes in the Communist ideology anymore. You might find a few people in Brown University or Harvard who still believe in Communism as an ideology, but you won’t find anybody in China, and certainly not in the Chinese Communist Party. However, they do believe in the Leninist structure of the state, in which the party is dominant, and that prescribes certain tactics, methods of control, and foreign policy techniques. For want of a better word, I would call them “united front tactics”. That means the use of other than state-to-state channels, cultural associations, business associations, literary associations etc., to gain influence—all Leninist states do this. The former Soviet Union did it up to the 1930s, when it was relatively isolated. By the 1950s, they by and large abandoned this because it was no longer isolated.

Now, post-Maoist China is certainly not isolated. But it still has United Front Work Department, which is under direct control of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party. And you have seen in recent times, for example in Australia, where they tried to subvert politicians and political parties. You saw it in New Zealand where—bless the souls of the Kiwis—a new citizen who became a member of parliament was found to have been an instructor in the PRC’s spy schools. I don’t know what their vetting process was like, but there’s possibly a reason why the Kiwis are an endangered species. And there are many other examples around the world. China is not just a normal state or a Leninist state. It also has a third identity of being a civilisational state—China is a civilisation, as well as a state, and that prescribes the third track. It’s a track that is of particular relevance for Singapore, and that is the overseas Chinese track. They also have a very elaborate institutional apparatus devoted to this track under party control.

The purpose of this track is best encapsulated by a speech President Xi Jinping made in 2014 to a conference of overseas Chinese business associations in Beijing. And the title of that speech was The Great Rejuvenation of the Chinese Nation is of Importance to all Chinese. In other words, the great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation is of importance to all Chinese means that overseas Chinese are expected, on crucial issues, to define their interests in terms of China’s interest. That is something a multi-racial country like Singapore can never accept. It is an existential issue. That’s why when a former senior civil servant says that a small country should behave like a small country— which is what the Chinese meant because you are a majority ethnic Chinese country—he has to be put down quite brutally, and not just by me, but by more important people than me.

SINGAPORE-CHINA RELATIONS: AN EXISTENTIAL ISSUE

Why is it an existential issue? It’s very simple because to align your interest with China’s interest means that you accept China, not merely as a geopolitical fact, but China’s superiority as a norm of international relations. Both concepts are very different. I mean everybody would accept China’s rise as a geopolitical fact. You have to be blind, deaf, dumb, and living on another planet not to do so. But that’s an entirely different matter from accepting China’s superiority as a norm of international relations. It is a very ancient norm of Chinese international relations, which is coming back, not exactly the same way as ancient times, but substantially the same. It manifests itself in big ways and small. Why can’t we accept that as a multi-racial country? China persistently refers to Singapore as a Chinese country. We persistently tell them we are not a Chinese country, but they persist. We cannot accept that. This is existential. That’s why the debate with the former civil servant is not just an academic or an intellectual debate. That’s why he has to be put down and brutally because it is a very small step from accepting China’s superiority as a geopolitical fact (“China” used as a proper noun. A big country, but still placed in a bounded territory) to accepting Chinese (“Chinese” as an adjective, which has no boundary) superiority as a norm. And you know what the regional and domestic consequences are.

By the way, I don’t think China is out to destroy Singapore. In some ways, they do admire Singapore because several Chinese and some Singaporeans who are very familiar with China have told me that the Chinese admires Singapore because it shows what the Chinese people can do after 100 years. However, they fundamentally do not understand why we are successful. That’s why they have a lot of problems with the Uyghurs and other minorities. No matter how good our relationship is on the first track (state-to-state relations), from time to time, they will try the other tracks, and they have never stopped. Sometimes it’s high-key and public, while at other times, it’s low-key and private. We have to resist such attempts even if it means roughing relations on the first track. That’s what happened over the last year or so. Now, they are playing nice again for a variety of reasons.

I will make two more points. The first point is, I said these kinds of things have never stopped in the 30 odd years I have been in the foreign ministry. Sometimes they are public, sometimes they are private. The last time it was public was in 2004. Why was it public? When then Deputy Prime Minister Lee Hsein Loong went to Taiwan, all hell broke loose. Now, that’s not the first time a Singapore leader has gone to Taiwan. They’ve gone many times, and the Chinese know well that no matter what, we know how to handle the One China policy. They do trust us when it suits them because some years ago, they came and asked us to do a free trade agreement with Taiwan because they were trying to prop up Ma Ying-jeou at that time. We don’t want a free trade agreement with Taiwan because it’s of no economic use. They asked us because they are confident that we know how to handle it without compromising the One China principle.

So what was their fuss in 2004 all about? It’s because it was quite clear, by that time, that Mr Lee Hsien Loong would be the successor to Mr Goh Chok Tong. One of the lies that the Chinese like to propagate on track two (united front tactics) and track three (overseas Chinese being for China’s interests) is that relations were so much better under Lee Kuan Yew, and these new people don’t know how to handle China. Mr Lee Kuan Yew did have good relations with many Chinese leaders including Deng Xiaoping. But why did he have good relations? There’s another fact that track two and track three of Chinese diplomacy never emphasises. Mr Lee Kuan Yew and the PAP is, as far as I can determine, and I have tried very hard to find an exception, the only non-Communist leader and party that went into a united front in the 1950s and 1960s with a Chinese Communist-supported party, the Barisan Socialis, and won. Every other non-Communist leader that went into the united front lost. And so, they had absolutely no doubt of Mr Lee Kuan Yew’s resolve, and that however friendly he is, he will be for Singapore first. But when there is a leadership transition, they wanted to see whether the son is made of the same mettle. They also tested Goh Chok Tong, by the way, in a less public way.

And this time, the last year and a half, there were many proximate causes for the tension. But it is also a time of succession because about a year ago, Mr Lee Hsein Loong announced that after the next election, he’ll step aside, and let the fourth generation of leaders choose who the next Prime Minister would be, and it is also meant to test them. They had no doubt about Mr Lee Kuan Yew. They put some pressure on Goh Chok Tong; didn’t work. They didn’t put much pressure because they probably thought he was the interim leader. They have a rather dynastic mindset which you can see, because there’s a category of Chinese leaders known as princelings. They tested Mr Lee Hsein Loong, it didn’t work. So now they are testing the fourth generation. The test isn’t over; they have paused for a variety of reasons and decided to play nice. Prime Minister had a very good visit to China, but that’s not the end of the story.

I told you state-to-state relations will always go up and down. There’s nothing to get too excited about. But it is conceivable, not very probable, that one day, as did the Soviet Union, China may give up the united front track. But China cannot give up the third track, the overseas Chinese track, without ceasing to be China, because it stems from the civilisational nature of the Chinese state. So we will have to learn to deal with this. How do we deal with this?

DEALING WITH CHINA

I think there are two fundamental things. One, is to have an educated public. It cannot be denied that a certain section of our compatriots who feel cultural affinity—nothing wrong with that—and therefore are either reluctant to acknowledge this track, or think there’s nothing wrong with it. I told you it’s a very small step from acknowledging China’s status as a big power, “China” as a proper noun, to using “Chinese” superiority as an adjective. We are only 52 years old. Are you absolutely confident that the Singaporean Chinese identity is so deeply rooted that none of our compatriots would be tempted, whether consciously or not, to take that small step? I’m not. Maybe in another 50 years, we don’t have to worry about it. But the experience of the last year and a half, shows me there are some who are tempted to take that step. So you have to deal with it, and the first way of dealing with it is to have an educated public.

Here, I have to acknowledge that there is something of a quandary. I can educate you in this closed group, and because I am a pensioner after all, I can say anything I want. I have a title that is meaningless. Don’t ask me what Ambassador-at-Large means because I have no idea. In the colloquial sense of the term, “at large” means not-yet-called. But I am a pensioner, I have no authority, I have no official position. So I can say what I just said to you. It’s very hard for a government to say these things because you don’t want to go and roil the official track unnecessarily. If it is necessary, of course, we have to hold firm to this fundamental bedrock of what makes Singapore, even if it causes tensions in the first track, and that’s what we did over the last year-and-a-half and 2004. A few months ago, Mr Chan Chun Sing was asked a question about foreign influence in politics in parliament. He had to give a very circumspect answer. So circumspect that, unless you already knew, you won’t know what he was talking about. I can’t blame him, you know? But in small groups like this, I can try to educate you.

The second big factor is to have a very clinical view of what’s happening in the world. One of the other Chinese lines is that China is rising. Therefore, your best friend, America, is declining. So you are the wrong side of history, and you better jump on this bandwagon. Now, that can’t be denied. I told you that you must be blind, deaf, dumb, and living on another planet to deny that China is rising. But it is wrong to look at China’s rise in simplistic and binary terms. There will be a more symmetrical strategic equation between the US and China sooner or later, but that doesn’t mean that the US is going to disappear from the world. It doesn’t mean that the US is going to cease to be a substantive country. And not just the US, but Japan as well. It doesn’t make much substantive difference if you are the biggest, second biggest, or third biggest economy in the world. You are all still going to be important players, and you all are going to be strong military powers. You all are going, in that sense, to deter, check, and balance each other. That gives small countries like us manoeuvre room.

Whether or not you’re going to be agile and clever enough to take advantage of the manoeuvre room is, of course, another matter. Nobody says we got to be clever, we can be stupid too, but the possibility exists. In other words, you can be small, and not behave like a small country, and preserve your autonomy. It is up to us.

Bilahari Kausikan is an Ambassador-at-Large at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA). Prior to this, he served at the MFA as Permanent Secretary from 2010–2013.