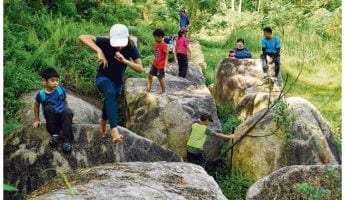

I could climb trees like a young chimp and if challenged, could even swing upside down from branches.

The quote is from the book Kampong Spirit Gotong Royong. Life in Potong Pasir, 1955 – 1965 by Josephine Chia, (pp. 62), depicting life in a Singapore kampong during the years leading up to independence.

The incredibly fast development that then followed as the city state transformed into a global financial centre includes tripling of the population, an increasingly urban life style and, perhaps not surprising, an increasing detachment of humans from nature. Though Singapore has retained quite a bit of green space for its citizens to enjoy, the interests of humans and wildlife tend to clash for example at new housing development on forested land. Reduced wildlife habitat leads to more human wildlife encounters, and indeed, complaints about wildlife are increasing every year in Singapore.

A recent study led by ASE’s Dr Kang Min Ngo, investigates how childhood nature exposure affects attitudes towards wildlife in Singaporean adults. Growing up in a highly urbanized environment can lead to a “self-reinforcing cycle where children that grow up in urban environments, with little exposure to nature, become estranged from nature as adults”. While in the kampong days it may have been different, today less than half of Singaporeans played in or visited natural environments as children, and only 15% did so frequently, Ngo’s study found.

Dr Ngo and co-authors wish to shed light on the human dimension of human-wildlife encounters, since it is the subjective human experience that determines what is successful wildlife management. Personal experience of wildlife encounters may vary depending on culture, level of education, age, gender and interest, as well as the animal in question. This study used interviews to investigate the attitudes of 1004 Singaporeans aged between 18 and 69, to long-tailed macaque, hornets and pythons, and then linked that to childhood nature experience using structural equation modelling.

The results showed that childhood nature experience was strongly linked to attitude, so that those who had more exposure to nature when they were young tended to be more positive towards wildlife as adults. The respondents were more positive towards long-tailed macaque compared to hornets and pythons. However, for pythons, gender was the strongest predictor of attitude, with females being more negative than males. Interestingly, some of the negative images people had of wildlife were unfounded and clearly not based on real experience, such as pythons being slimy and poisonous, leading to irrational fears.

The good news is that there is plenty that can be done to help relieve fears and change attitudes, like direct participation in nature activities. Dr Ngo hopes that good planning and education can make Singaporean residents more willing to coexist with wildlife as Singapore develops, and maybe even appreciate the proximity to nature that kampong life once used to offer, so that green spaces that harbour wildlife can be preserved.

Dr Kang Min Ngo is a Research Coordinator and Assistant Director with the NTU-Smithsonian research partnership, Asian School of the Environment, NTU.