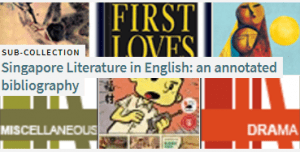

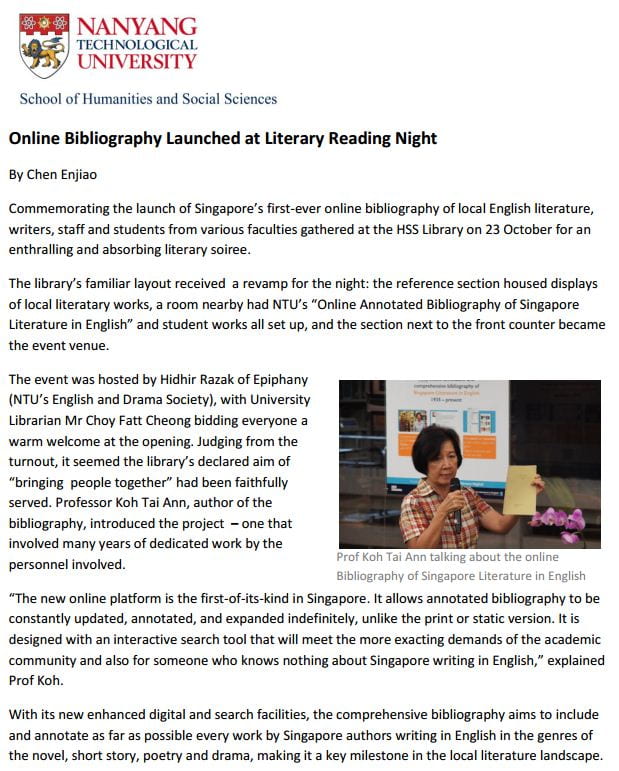

‘Night at HSSL’ & Online Bibliography Launch Event:

Title and Scope of the Annotated Bibliography

Why not “Creative Writing in English”?

Previous bibliographies used to modestly describe the literature as “Singapore Creative Writing”, which might suggest today a body of writing by new or apprentice writers still developing their craft and which literary-critical opinion was not ready yet to regard as “Literature”. Since the publication of the last print bibliography thus titled – the National Library’s Celebrations: Singapore Creative Writing in English by Gene Tan – the term, “creative writing” is no longer an adequate and is even possibly, a misleading description. It is now more usually associated in Singapore with writing competitions, workshops or a medium used in educational institutions to foster language learning and/or self-expression. Moreover, in recent years, local tertiary institutions have started offering undergraduate creative writing courses as part of the subject, English Literature, or as a graduate programme in its own right where students produce their own “creative writing” instead of academic theses to earn their degrees.

Why “Literature in English”?

(a) Since the publication of the first short mimeographed “bibliographies of creative writing” (by the National Library and the then University of Singapore Library, both coincidentally in 1976) a core of writing in English has steadily grown in quantity and quality in tandem with its maturing creators and the emergence of new talent. In literary achievement such work undoubtedly qualifies as “Literature”. The works of Singaporean writers in English now feature both in the curricula of local university English Literature departments and of universities elsewhere, are studied as one of the “Literatures in English” or as post-colonial texts. Although literary canons are contestable and no longer in fashion, canon-formation covertly goes on none the less. A literary canon of Singapore writers in English is already discernible based on reputations established by critical acclaim such as favourable reviews, inclusion of their work in anthologies and periodicals, studies of their work in academic articles and books, invitations to participate in national and international literary festivals, media attention and so on.

(b) Meanwhile, a new literature of a young nation and small city state like Singapore renders it possible still to identify and include within one handy volume (the bibliography having appeared originally in print) every title published since ‘local’ (as distinct from expatriate) writers began publishing literary works in English. These appeared sporadically from the late 19th Century, but steadily grew in quantity from the postwar years of the late 1940s, making it practical – albeit still arduous – to compile and annotate an inclusive, comprehensive, even possibly, a complete bibliography of the literature at any selected point in time up to the present. The “Literature” in the Bibliography’s title therefore also means literature in the generic sense of writing in any of the main literary forms – novels, short stories, poems and plays in English ever published by Singaporean writers.

Why “Singapore” and not “Singaporean Literature in English”?

What accounts for the hesitancy of the description in the title “Singapore” and not “Singaporean” Literature in English, when we have “Singaporean” writers? This follows the precedent of previous bibliographies, which in turn was determined by the fact that Singapore has four official languages (Malay, Chinese, Tamil and English) each with its own literature. None can therefore lay claim to be the “national literature” such as to own the epithet, ‘Singaporean’: each therefore is a literature of Singapore in a particular official language. However, these literatures collectively are described and known as “Singaporean Literature”.

None the less, while English may not be the national language and is only one of four official languages, its being the official working language of government and commerce and sole medium of instruction in Singapore’s national school system makes this virtually a national bibliography. Collectively, the items in this bibliography could be said to comprise a literary history and collectively portray a Singaporean identity expressed in English and in the local dialect of English, Singlish.

Scope: How Comprehensive?

(a) The Bibliography aims to be comprehensive to the point of being a complete record and, moreover, has an archival function. Apart from volumes and works published by individual authors, it includes unpublished typescripts or manuscripts deposited with and catalogued in the Singapore National Library, as well as works which first appeared in periodicals, are found in anthologies and even in ephemera such as programmes of readings where poems by then young, unknown writers, originally found their way into print. Being comprehensive, the bibliography also includes “creative writing” by many a beginner or apprentice writer, usually students. Such writing is most often to be found in anthologies published by schools, or those resulting from “creative writing” or literary competitions, workshops and the increasing number of mentored writing programmes for aspiring young writers. Significantly, in such anthologies will be found the “creative writing” of fledgling poets who have since gone on to publish their own collections – such as Angeline Yap, Toh Hsien Min, Alfian Sa’at and others – just as the youthful work of the pioneering and previous generation of writers such as Edwin Thumboo, Arthur Yap and Lee Tzu Pheng had first appeared in undergraduate and other periodicals as well as anthologies from the 1950s to the 1970s.

(b) The Bibliography is totally inclusive. When a former colleague heard that the compiler was working on the bibliography he thought ‘it would certainly help fill in a lot of gaps’ but added that his ‘impression is that much of the literature was not of lasting interest.’ This bibliography does indeed ‘fill in a lot of gaps’ in previous bibliographies and attempts much more besides; but it makes no literary-critical or such judgments, leaving that to readers, time and posterity.

(c) Errors and Omissions are possible. While the bibliography aims to be as comprehensive, inclusive and up to date as possible, inadvertent omissions and errors are quite possible. It is hoped users of the Bibliography will draw these to our attention. Unlike the original 2008 print edition and all its print predecessors, a digital bibliography can be amended, updated and expanded speedily, continually and indefinitely online.

Singapore Literature in English : an annotated bibliography

Compiler and Editor

Professor Koh Tai Ann

College of Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences

Nanyang Technological University

Singapore Literature in English: an annotated bibliography, 2008

Archived in NTU Digital Repository

Related links

Quarterly Literary Review Singapore

Singapore Book Council Resources

NAC (National Arts Council) Researcher Directory

Contemporary Post-colonial and Post-imperial Literature in English

Online Resources

National Library of Singapore Catalogue

National Library of Singapore Resource Guide – Literary Arts

More Resources

Yearly Annual Bibliography of Commonwealth Literature, Malaysia and Singapore section by Ismail S. Talib in Literature, Critique, and Empire Today (Previously the The Journal of Commonwealth Literature)