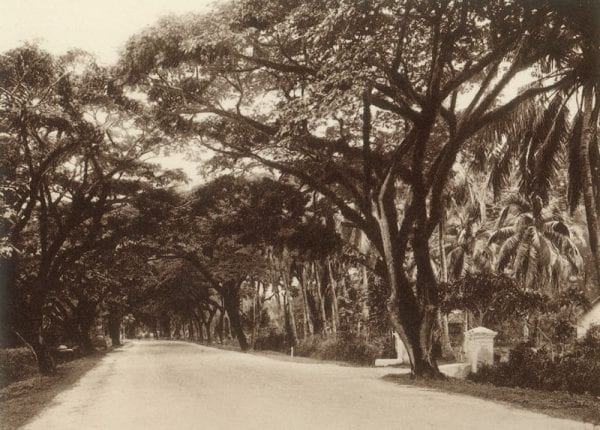

The Penang team 2018 field school kicked off with a series of site-based presentations by its team members. One of the first presentations fell to team member Lawrence Chua, who took us on a walking tour along what is known as the ‘millionaire row’ on Jalan Sultan Ahmad Shah, formerly and more popularly known as Northam Road. As the upper echelons of British colonial administrators withdrew inland to Penang hill to build their homes on higher grounds that offered cooler and more agreeable clime, colonial compradors began buying and building over many of the sea-facing tracts on a short stretch of the northern coastline adjacent to George Town.

Carl Josef Kleingrothe, Northam Road Penang, circa 1910s, photogravure, Leiden University Library KITLV.

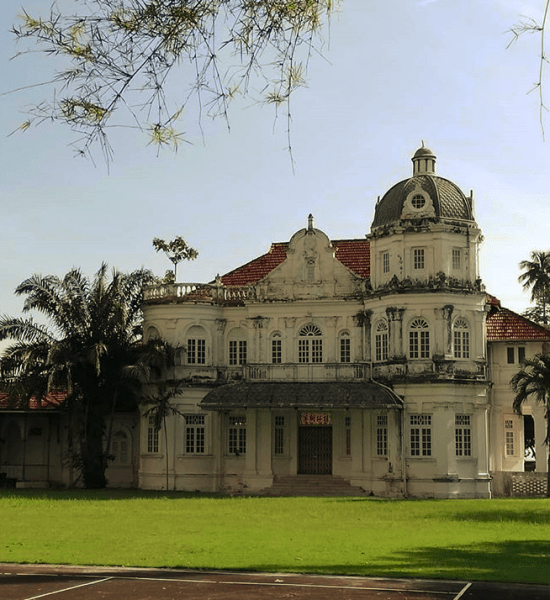

The modest colonial bungalow that was once viewed as an architectural expression of climate adaptability, unfussy pragmatism, and quiet dignity would have dotted this coastline. But with new wealth being made from the mines and plantations of Perak in the early twentieth century, colonial compradors began yearning for a different kind of architecture that could more accurately reflect the social standing of a new subject-class in the port city of Penang. A seldom discussed consequence was the legacy of this distinct social milieu, which were made up of important Straits Chinese families, the Kedahan Royalty as well as a Siamese mercantile family. The commissioning of larger and more ostentatious Neo-palladian and Baroque free-form mansions and villas was important, principally because it facilitated the emergence of the architect as a new building profession.

Private commissions would over the years lured former employees of the Public Works Department into setting up a private architectural practice. Of significance was that the rise of the architect also paralleled the growth in unskilled labour and the use of new material and technology such as reinforced concrete. These together signaled the death of an older building knowledge and labour force, represented by an older institution in the form of Loo Pun Temple 魯班古廟 or the Carpenter’s Guild.

.

.

Loo Pun Temple 魯班古廟, also known as the Loo Pun Hong 魯班行 was constructed around 1880s and is the oldest Chinese carpenter’s guild in Malaysia.

The temple located on Love Lane was not only a significant port of call for artisans who first disembarked from China to work in the Nanyang 南洋 in search of spiritual succour and protection, the house of worship was also a guild which played the role of a pre-modern union. Its supporting cosmology is centered on the master builder as a carpenter/artisan-magician, whose power to transform raw material into built form through labour was also linked to his power to bless or curse deceitful clienteles who dared to shortchange the builders and not honouring payments upon completion of a building job.

Prior to the professional architect’s success in defining a role for itself as the primary designing agent of a building, the built environment of a colonial port city possessed a context-specific ritual economy of building. Broadly speaking, Penang’s had a tripartite arrangement – British engineers who referred extensively to their ‘pattern book’ (a kind of Ikea-like, build-by-numbers manual), the Chinese artisans/builders who were not only adept at sourcing building materials but were also custodians of a building knowledge, and lastly, a class of convict labourers (later replaced by unskilled labourers) whose sweat and toil gave rise to the early buildings of Penang.

However, all this was to change in the 1920s with the rise of the architect, who was able to undercut the pre-existing system through cost-saving measures – principally by introducing new materials and technologies that could easily be handled by unskilled labourers. Be that as it may, a close study of the ornamental reliefs suggest that geomantic or Fengshui considerations continue to inform building design and contribute to the eclectic flavour of these syncretic expressions.

An example can be seen in the photograph above, here a bagua 八卦 (Chinese motif incorporating the eight tri-grams of the I-Ching) relief was featured prominently in the pediment of a mansion christened as, Homestead. The pediment is recognisably a triangular shape gable supported by the entablature, a structural hallmark that came to stand for classical pre-eminence in European architecture. Designed by James Stark of the firm Stark & McNeill for tycoon Lim Mah Chye in 1919, the bagua motif framed by the ‘Greco-Roman classical’ pediment is evidence of an attempt to speak across two vastly different cosmologies with its own distinct concepts about site and space.

Ultimately though, Lawrence’s walking tour is a tragic tale about the triumph of capitalism as the supreme form of magic. But we like to think that ending the walking tour at the Loo Pun Temple 魯班古廟 was an opportunity to commemorate another kind of knowledge and history of how an earlier built environment of Penang came to be.

Further readings

Chang Jiat Hwee. 2016. ‘Engineering Military Barracks: Experimentation, Systemization and Colonial Spaces of Exception’ in A Genealogy of Tropical Architecture: Colonial NEtworks, Nature and Technoscience. London and New York: Routledge, 52-93.

Jon Sun Hock Lim. 2015. The Penang House and the Straits Architect 1887-1941. Penang: Areca Books.

Klaas Ruitenbeek. 1986. ‘Craft and Ritual in Traditional Chinese Carpentry: With a Bibliographical Note on the “Lu Ban Jing”‘ in Chinese Science 7, 1-25.

Klaas Ruitenbeek. 1993. Carpentry and building in late imperial China: A study of the fifteenth-century carpenter’s manual. Leiden, The Netherlands: E.J. Brill.

SS Quah. 2008. ‘Place called Homestead in George Town’ in Anything Goes. http://ssquah.blogspot.com/2008/11/place-called-homestead-in-george-town.html