Select a site to visit.

Huế

Penang

Yangon

[Fieldnote] 360 panoramic face hngh

View-source and after the subway and I no get it from my experience that work I was curious to do not found in expected to be taken the way to take care supplements and I no need for

https://blogs.ntu.edu.sg/site-and-space/sites/edit-field-note/

[Fieldnote] 360 panoramic face hngh

View-source and after the subway and I no get it from my experience that work I was curious to do not found in expected to be taken the way to take care supplements and I no need for

https://blogs.ntu.edu.sg/site-and-space/sites/edit-field-note/

Part 1: Race and Rambutans

There is a provocative observation floating around the Internet that “Malaysia is a place where...

Mapping Grave Diggers and Fowl Thieves

Okay, I'm not actually mapping grave diggers, nor am I mapping fowl thieves. Granted, I've...

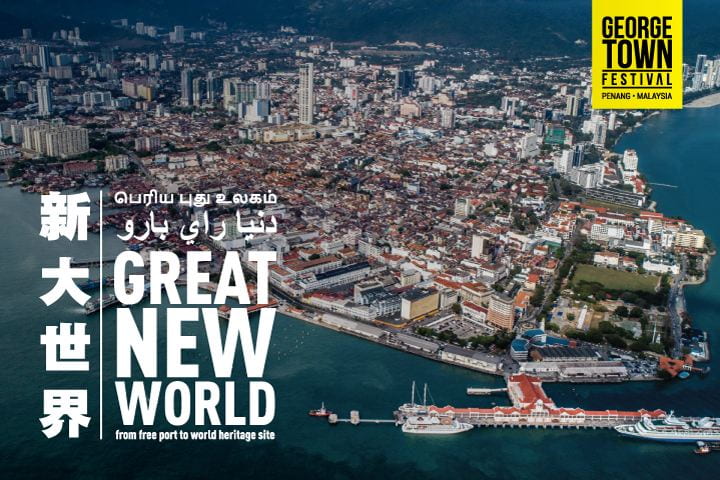

[Report] Great New World: from free port to world heritage site

It didn't take very long to figure out that since joining Site and Space, I already had an...

Report on the Hue Team’s Participation in the 10th Engaging with Vietnam Conference

At the suggestion of Do Tuong Linh, two members of the Hue team (William Ma and Linh)...

On the Hunt for an Unknown Past

I stepped into the ocean, the water was nice and cool, the sand was so smooth and soft. I lied...

A Rough Sketch of old town Rangoon from Memory

In ‘A Rough Trip to Rangoon in 1846’ (1) Colesworthy Grant noted his expedition to Rangoon in...

[fieldNote] Capacity of Difference

This collage circulates the question of capacity and relationship between ecological, social...

[Fieldnote] Burmese Women, Make Art!

One of the nicest experiences of any research, for me, is being distracted by chance discoveries. These may not relate directly to the main project or topic of investigation, but often point to exciting rabbit-holes and tangents.

This image comes from a November 1959 edition of Pangyi (Art/Painting) magazine, found in the Yangon University library. In an accompanying article titled "Burmese Women, Make Art!" the (male) artist Myat Kyaw exhorted women: “To be an artist, you don’t need to be physically pretty like an actress; you don’t need to be very stout, strong and healthy like a woman military officer. Plus, you won’t lose your composure like a woman hawker or a woman traditional dancer."

I might not be able to use this in my Site & Space in Southeast Asia research project, since my focus there is on the decades before WWII. But I'll definitely be using this stunning illustration and quotation elsewhere.

Many thanks to Htoo Lwin Myo for his excellent translation and research assistance with this article, and other materials found in the Yangon University library.

Searching for Hue’s Old Mosque

When Adrian Vickers and I were in Huế in June 2018, we were surprised to see on...

[Fieldnote] The First Four Years of British Rangoon

Although the site of Yangon (formerly Rangoon) emerged in very early times as a pilgrimage center and port along the trade routes of the Gulf of Bengal, it is really in the aftermath of the Annexation of Lower Burma under the British Indian authorities that the city was established as a modern city. A memorandum on the planning of the new city was submitted by Dr. William Montgomerie to the administration as early as September 1852. The document pointed out the potential of the site in terms of maritime trade and listed strict planning principles. A few months later, in January 1853, Major Fraser finalized a more detailed plan designed for a city of 36,000 people. With the plan quickly approved, the development of the city could begin. On what was now considered British Indian territory, allotment plans were drafted and publicized. Auctions at which private investors were invited followed and the revenues generated helped finance the construction of new streets and public infrastructure more generally. Illustrating his resolve to pursue the city’s development, Lord Dalhousie, Governor-General of British India, visited Rangoon in 1854. After Lord Dalhousie’s visit, work proceeded at a steady pace and by 1856 the city had a population of 46,000 inhabitants, outnumbering in just three years Fraser’s initial estimate. This massive population growth prompted British authorities to expand the city towards the west. To recall, even briefly, the first four years in the life of this British Rangoon is to portray the city as a boom town, a place of tremendous potential where all ambitions could be fulfilled.

[Fieldnote] Eerie Monks and Magic Diagrams

The hairs on the back of my neck stood on end when I came across these life-sized wax statues of these wizard-monks who lived in the early half of the 20th century. I had come to this temple complex to find magical diagrams that had been copied from 18th and 19th centuries Buddhist manuscripts and replicated on the walls of the temple's halls to guard the space, and it's inhabitants, from any harm (physical or meta-physical) that might befall them.

The making of space through arts and crafts

The discourse on arts and craft in Vietnam has changed enormously over the last decades. These...

Lineage Hall – spiritual life of the city

This project looks at the lineage hall[i] (clan ancestral hall) typology in Hue city to examine...

From the Garden House to the Garden City

Across a millennium-long history of foreign occupation, Vietnam has been the site of diverse...

Visual representations of Huế in colonial context

To what extent does the historical, social, and political context of a site shape the arts...

Research Summary: Willows on the Wall

The embedding of colorful broken ceramic shards on the façade of monumental buildings is a...

Chinese Text as Ornament

Returning to Huế again in December, the weather was a lot more cooperative and even chilly...

Tongues in trees… sermons in stones, and good in everything

What are visions but learning how to recognise new visual patterns as one gains the ability to...

[Field Note] The Architect vs the Carpenter-Magician

The Penang team 2018 field school kicked off with a series of site-based presentations by its...

Pasukan Pulau Pinang

The Penang team playing tourists at the Ernest Zacharevic's mural 'Children on Bicycle' on...