6. Conclusion

This chapter has hoped to highlight to the reader the complex nature of the subject matter of linguistic complexity. While we have presented certain models and frameworks used to approach the subject matter, it is crucial to note that the linguistic community as a whole does not have a recognised model. This is thus a very important facet of linguistic complexity that require much further research before any more exploration of the topic may continue.

Linguistic complexity holds much value in terms of language learning and acquisition. It also has the ability to feature in other aspects of linguistics such as historical linguistics as so more research does hold benefits.

We have also tried to make it as accessible as possible and hope that linguistically and non-linguistically inclined readers learn something from our blog. We hope that you learn as much from reading this chapter as we have.

Thank You,

Sathrin and Sabrina

7. References

Akker, Peter (1987). Reduplications in Saramaccan. In Mervyn C. Alleyne (ed.), Studies in Saramaccan Language Structure, 17–40. Amsterdam: Instituut voor Algemene Taalwetenschap.

Chomsky, Noam 1965. Aspects of the theory of syntax. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Chomsky, Noam and Morris Halle 1968. Sound pattern of English. New York: Harper and Row.

Dahl, O. (Director) Lectures on linguistic complexity. Lecture conducted from , Stockholm.

Dahl, Ö. 2004. The growth and maintenance of linguistic complexity. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Edmonds, B. 1999. Syntactic measures of complexity. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Manchester.

Dworkin, R. (2002). Sovereign virtue: the theory and practice of equality. Harvard University Press.

Gell-Mann, M. 1995. What is complexity? Complexity 1(1): 16-19.

Hawkins, John A. 2004. Efficiency and complexity in grammars. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hawkins, John A. 2009. An efficiency theory of complexity and related phenomena. In Geoffrey Sampson, David Gil, and Peter Trudgill (eds.), Language complexity as an evolving variable, 252-268. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hübler, Alfred W. 2007. Understanding complex systems. Complexity 12(5): 9-11.

Kiparsky, Paul 1997. The rise of positional licensing. In Ans van Kemenade and Nigel Vincent (eds.), Parameters of morphosyntactic change, 460-494. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kusters, W. 2003. Linguistic complexity: The influence of social change on verbal inflection. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Leiden.

Lloyd, S. 2001. Measures of complexity: A nonexhaustive list. IEEE Control Systems Magazine 21(4): 7-8.

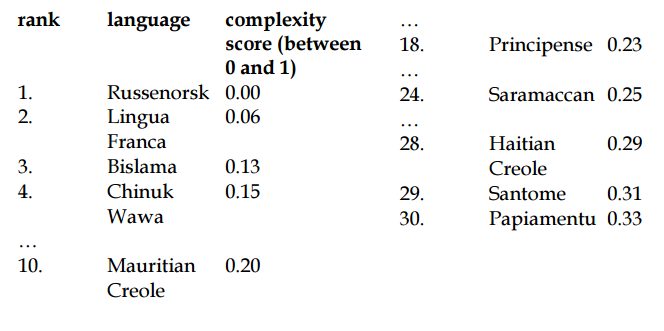

McWhorter, John H. (1998). Identifying the creole prototype: Vindicating a typological class. Language 74: 788– 818.

McWhorter, John H. (2001). The rest of the story: Restoring pidginization to creole genesis theory. Journal of Pidgin and Creole Languages.

Miestamo, M. 2008. Grammatical complexity in a cross-linguistic perspective. In M. Miestamo, K. Sinnemäki, and F. Karlsson (eds.), Language complexity: Typology, contact, change, 23-41. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Pallotti, G. (2014). A simple view of linguistic complexity. Second Language Research, 0267658314536435

Parkvall, Mikael 2008. The simplicity of creoles in a cross-linguistic perspective. In Matti Miestamo, Kaius Sinnemäki, and Fred Karlsson (eds.), Language complexity: Typology, contact, change, 265-285. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Prideaux, Gary D. 1970. On the selection problem. Research on Language & Social Interaction 2(2): 238-266.

Rescher, N. 1998. Complexity: A philosophical overview. New Brunswick: Transaction.

Simon, Herbert A. 1996. The sciences of the artificial (3rd edn). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Sinnemäki, K. 2008. Complexity trade-offs in core argument marking. In M. Miestamo, K. Sinnemäki, and F. Karlsson (eds.), Language complexity: Typology, contact, change, 67- 88. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

Sinnemäki, K. 2011. Language universals and linguistic complexity Three case studies in core argument marking. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Helsinki. Available at https://helda.helsinki.fi/handle/10138/27782.

Steger, M. & Schneider, E. (2012). Complexity as a function of iconicity – The case of complement clause constructions in New Englishes. In Bernd Kortmann and Benedikt Szmrecsanyi (eds.), Linguistic complexity: second language acquisition, indigenization, contact. (pp. 156-191). Berlin: Boston: Walter de Gruyter, 2012