In July 2020, our lab director, Asst Prof Suzy Styles and Research Associate Eshwaaree presented at the virtual conference organized by the International Congress of Infant Studies (ICIS 2020). They presented a systematic review on parent-child speech and early language development outcomes.

Substantial literature investigating the relationship between a child’s language development and the speech they hear from their caregivers has been published over the years. In the 1990s, Hart and Risley published an influential study investigating parental speech inputs and predictions on later language outcomes – popularising the idea of a “30 million word gap” between children who received less speech input from their parents compared to their peers.

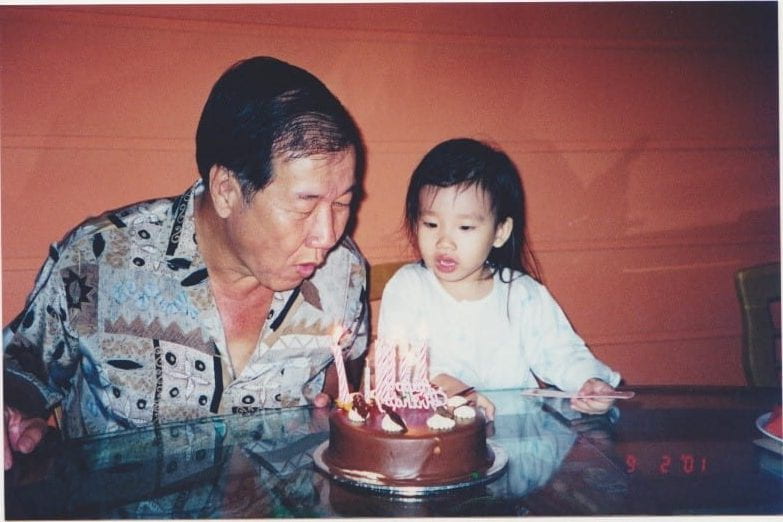

Since then, many studies have further explored this relationship – higher quantity and quality of speech heard in the early years is associated with more proficient language skills. However, in correlational designs like this, there are always other possible causal pathways as shown in the graphic:

Pathway A – the quantity/quality of parent talk influences child language outcomes (e.g., talking more helps a baby develop language skills);

Pathway B – endogenous child language skills influence the quantity/quality of caregiver talk (e.g., a chatty child elicits more speech);

Pathway C – external factors influence both parent talk and child language development independently (e.g., environmental factors such as poverty-induced stress).

A systematic review of peer reviewed journal articles from 1977 to 2018 was conducted to examine the prevalence of interpretation bias for these three possible pathways. We found that most studies report Pathway A and a notably low number of articles were found to mention other causal pathways. This finding demonstrates that reporting habits in this field are biased towards the interpretation that ‘speaking more to a baby will enhance their language development’. This interpretive bias has potential implications for parents, educators and policy makers, as scarce resources may be invested in interventions targeting one causal pathway (e.g., talking more to babies), while others are overlooked (e.g., alleviating poverty in families most at risk).

This finding demonstrates that reporting habits in this field are biased towards the interpretation that ‘speaking more to a baby will enhance their language development’.

Findings from our systematic review revealed this reporting bias and has led us to come up with a novel intervention study – Talk Together Study. We want to find out more about the pathways linking parent-child talk to child language outcomes and the efficacy of a “talk-boosting intervention”.

Click here to find out more and click here if you’re a parent of a child 8-36 months old and interested to sign up!

Photo by Chevanon Photography from Pexels