Photo by Tj Holowaychuk on Unsplash

Christmas in my household has always been “different”. My family has our own set of traditions, almost bordering on idiosyncrasy. We celebrate Christmas on the 24th, eat sushi with our Christmas ham, and stay up late to count down to Christmas like one does for the new year.

This year, the Christmas (eve) dinner felt different. It was quieter and more subdued. Our dinner conversation revolved around vaccines and embarrassing stories of telecommuting. Nothing a good old-fashioned biomedical lesson (with a sprinkle of statistics) to put your language skills in place. My mother only speaks Mandarin and Hokkien, armed with a handful of English phrases she picked up from watching American TV crime shows. After many rounds of poor translations from my sister and I, we managed to convey the technology of the mRNA vaccine, though I am pretty sure we did its sophistication no justice. My mother marvelled at its technology and described the old-school vaccines she had in the 70s which left scars (we never quite figured out what it was for – smallpox? BCG?) that served as a physical mark for her generation. By the end of the dinner, over some homemade chocolate pudding, we were discussing our favourite YouTube cooking channels, while I translated cooking terms between Mandarin and English for my sister and her.

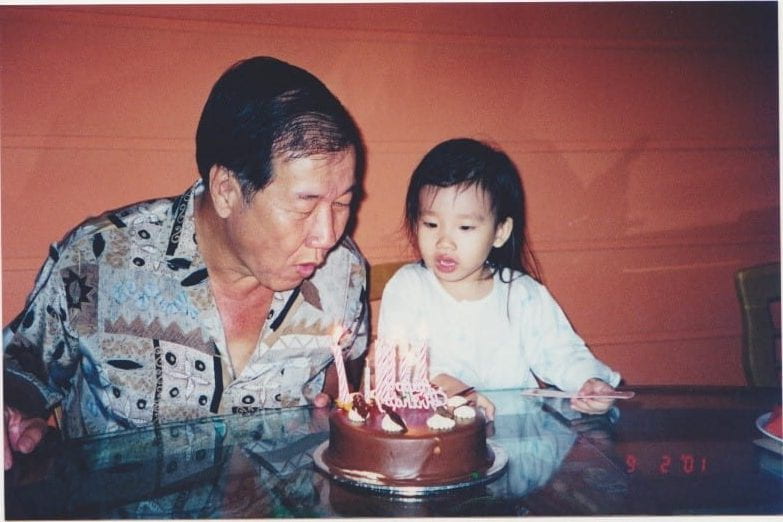

Family conversations in my household have always been like this growing up, we switch from one topic to another and trade in English, Mandarin and Hokkien. We pause, hemming and hawing, searching for an equivalent (or close enough) word to get our stories across. We always managed to accommodate, switch between languages and translate on the fly. Sometimes my sister, my father and I talk in rapid-fire English and I see my mother smiling and nodding; I would translate to her what was said briefly, and she would tell me she kind of understood.

I think a lot about my proficiency in Hokkien, and how it mirrors my mother’s proficiency in English. I produce a few words and understand a whole lot more. I can’t put my finger on why it bothers me a little that I am not proficient in it, or what being proficient in it really means to me. It reminds me of an early childhood memory, standing in the kitchen, making a conscious choice to pick up Hokkien so I could “be an adult” and speak with my grandmother who lived with us.

Now, years after she passed, I hardly use it anymore. I still use Hokkien now and then, a smattering of phrases at home, a listening aid for eavesdropping on conversations in public. I hold onto these bits and pieces of Hokkien, even when my parents and peers tell me how “weird” and “uncouth” it sounds. I think, now, mostly, it reminds me of my grandmother smiling and nodding at my little bits of Hokkien mixed with Mandarin.

This post was written by our research assistant Victoria, BLIP lab’s newest member! She’s currently working on the language mixes project. Besides English, Victoria also knows Mandarin, Hokkien, and a little bit of Japanese.