Mock chicken (mock meat) is a vegetarian food, made of wheat gluten and marinated in soy sauce. Wheat Gluten (麵筋, Mian Jin) or commonly referred as Seitan, is rich in protein, phosphorous, selenium and iron, hence it is commonly used as meat analogues or meat substitutes, and also provide as an alternative to soybean based products like dou fu (豆腐). In Buddhist and Asian vegetarian cuisines, we can often find mock meat and wheat gluten in place of meat. There are various preparations and Chinese recipes for wheat gluten, including oil frying, braising and steaming.

In some Chinese recipes, wheat gluten is oil fried into crispy dehydrated golden-brown wheat gluten balls, and later cooked in stir fried vegetable dishes or braised in flavourful stews and soup as “imitation abalones”.[1]

Another way of cooking is to steam raw wheat gluten/ vital wheat gluten in a sausage form for around an hour and slice it thickly into medallions, bearing some resemblance to the texture and appearance of chicken slices.[2]

The history of wheat gluten as a mock meat dates back to 6th century in China, where Buddhism vegetarian dietary laws encouraged the innovation of wheat gluten dishes as meat analogues to substitute meat-based dishes for the Buddhists. Some schools and sects of Buddhism allowed Buddhist disciples to consume flesh, if they did not kill the animal or if the animal is not killed for their sake.[3] However, according to stricter Mahayana scriptures from India, namely Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra, the Lankavatara Sutra and the Brahma’s Net, Buddha disciples are strictly forbidden to consume meat under the justifications of karma, reincarnation and elimination of one’s capacity of compassion.[4] The spread of Buddhism through Buddhist missionaries from India to China during this period welcomed new Buddhist knowledge and the enforcement of strict Buddhist dietary rules like vegetarianism (Su, 素) in China.[5]

The spread of Buddhism and vegetarianism in China heightened around fifth to eight centuries, especially in the fifth century when Emperor Wu of southern Yangtze region exercised the prohibition animal sacrifice and edict monks to comply to meat abstention, and with the incorporation of Buddhism in state rituals by later rulers. [6] The creation and innovation of meat analogues was later spurred by responses of Buddhists devotees or lay people who only maintained a vegetarian diet for certain occasions like on first half of three months and on six other special days every month.[7]

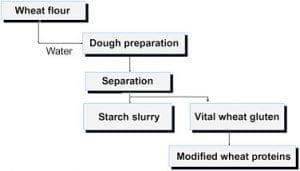

The wheat gluten is made through tedious kneading and washing wheat flour dough to remove all starch granules, resulting in a sticky and elastic dough.[8] Through traditional cooking methods of boiling, frying, pickling and smoking, wheat gluten was modified to resemble chicken and other meat, and served as a specialty at monasteries.[9] According to novels and accounts of imperial period, monks and Buddhist lay people hosted and devised a plethora of banquet mock meat made of wheat gluten, to replicate the texture and taste of pork shoulders and lamb legs in consideration of their meat eater patrons.[10] Buddhists fostered the success of wheat gluten in China through their constant experimentation and innovation with wheat flour in creating new vegetarian dishes.[11]

In today’s context, it is hard to get freshly cooked wheat gluten or mock meat unless you visit a vegetarian or Buddhist restaurant. Now, cooking mock meat is not as time consuming and tedious as compared to the past. Wheat gluten are manufactured in various processed forms including powdered, canned and dried. Mock meat and wheat gluten are now commercialized and easily available to mock meat enthusiasts and vegetarians in different forms on shelves at supermarkets or groceries store. Vital wheat gluten often found in supermarkets and used in bread recipes, actually derived from a manufacturing process whereby wheat flour is hydrated for the activation of gluten and subsequently then dried and grounded back into a powder form.

Furthermore, cooking enthusiasts could easily purchase wheat gluten packaged in dried or fried forms and spontaneously whip traditional Chinese recipes like Hong Shao Kao Fu, (红烧烤麸) or stir fried gluten balls with vegetables.

Lastly, for busy for the convenience of those with busy lifestyles, wheat gluten is processed with sugar, Monosodium Glutamate (MSG), Salt, Soy Bean Oil and Soy Sauce and manufactured into canned mock meat for hassle free consumption.

Conclusively, due to the influence of Buddhist dietary rules in China, the Chinese and Buddhists used traditional cooking techniques to transform plant materials like wheat flour into new forms of ingredients like wheat gluten consideration of its taste and flexibility. The use of wheat gluten in creating mock meat laid the foundation of su (素) cooking in China’s Buddhist cuisine and marked China’s expertise in technical and culinary innovation that is distinctive and unrivaled with other societies.[12

Bibliography:

[1] “Northern cuisine Stir Fried Baby Bok Choy with Gluten Balls (油菜炒面筋)”, (Omnivores cookbook), Accessed September 15, 2019, https://omnivorescookbook.com/stir-fried-baby-bok-choy-gluten-balls/

[2] “How to make vegan wheat meat chicken-style seitan”, (livekindly, 2018), Accessed September 15, 2019, https://www.livekindly.co/vegan-chicken-style-seitan/

[3] John Kieschnick, “Buddhist Vegetarianism in China”, In Of Tripod and Palate

Food, Politics, and Religion in Traditional China (Palgrave Macmillan, New York, 2015) : 187, Accessed September 15, 2019, https://link.springer.com.remotexs.ntu.edu.sg/chapter/10.1057/9781403979278_10

[4] Kieschnick, “Buddhist Vegetarianism in China”,190-191

[5] ANDERSON, E. N. “Foods from the West: Medieval China.” In Food and Environment in Early and Medieval China (University of Pennsylvania Press, 2014): 170. . Accessed September 15, 2019, https://www.jstor.org.remotexs.ntu.edu.sg/stable/pdf/j.ctt83jhpt.11.pdf?ab_segments=0%2Fl2b_100k_with_tbsub%2Fcontrol&refreqid=search%3Adf3bb760dc9210656e059c08f6b7f2f9

[6] Laudan, Rachel. “Monks and Monasteries: Buddhism Transforms the Cuisine of China, 200 CE—850 CE,” In Cuisine and Empire: Cooking in World History (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013), Ch. 3: 166 (Week 6 class reading in black board)

[7] Kieschnick, “Buddhist Vegetarianism in China”, 205

[8] Sabban, Françoise, and Elborg Forster. “China.” The Cambridge World History of Food. Eds. Kiple, Kenneth F. and Kriemhild Coneè Ornelas. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

V.B.3: 1170-1171 , Accessed September 15, 2019, https://www.cambridge.org.remotexs.ntu.edu.sg/core/books/cambridge-world-history-offood/china/6C7996C7EAD454219D3546B4D61DEA55

[9] Laudan, Rachel. “Monks and Monasteries: Buddhism Transforms the Cuisine of China, 200 CE—850 CE,” 172

[10] Kieschnick, “Buddhist Vegetarianism in China”, 205

[11] Thomas. “Soybean.” In The Cambridge World History of Food. Eds. Kiple, Kenneth F. and

Kriemhild Coneè Ornelas. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000). 423. Accessed September 15, 2019,

https://www.cambridge.org.remotexs.ntu.edu.sg/core/books/cambridge-world-history-offood/soybean/31B3DFEF9DDC9C52A3DA5C867D8282EF

[12] Françoise, and Elborg Forster. “China.” , 1170-1171

[13] “Wheat Gluten”, (Biopolymers for Food Design, 2018), Accessed September 15, 2019, https://www.sciencedirect.com/topics/agricultural-and-biological-sciences/wheat-gluten