wikimedia 2012

Like many foods we encountered this semester, there are many varying myths on how the food came to be, wonton noodle is no exception. One myth on wonton dates back to the Han Dynasty, in which it was first called huntun (Mandarin).[1] It was said that during the Han dynasty, the Xiong Nu people kept creating trouble for the general populace. The leaders of the Xiong Nu people also bore the last names of hun and tun. Out of desperation, people began stuffing meat fillings into bing (foodstuff made from wheat flour)[2], call it huntun and ate it, hoping for peace. This coincided with the winter solstice, making it a tradition to have dumplings every winter solstice.

“tang dai xi yu de jiao zi yu hun tun 唐代西域的饺子与馄,” [Jiaozi and Wonton in the Western Region of Tang Dynasty], China Xinjiang, 6 February 2019In the Zhuangzi though, there exists a different reason as to why wonton may be called huntun. The Zhuangzi explains that one of out of the three emperors was called Wonton, the emperor of the centre. It was believed that everyone has seven holes for daily functions such as breathing and eating and yet Wonton does not have any.[3] Wanting to repay Wonton’s kindness towards them, the other two emperors decided to bore seven holes on him. To their dismay, Wonton died after the seventh hole was drilled on him. This story talks about the concept of huntun or “cosmic chaos”, a fundamental concept in Taoist mythology. Taoism was also the official religion in the Tang Dynasty. Eating wonton soup was supposed to be an act of being harmonious with nature, evidenced by its mixed fillings (of meat and vegetables and wrapped in translucent and wrinkly skin) and soup.[4] This is why ancients also considered wonton a sealed dumpling (like Wonton the emperor with no holes). Disturbing this equilibrium will result in dire consequences (Wonton’s death). Wonton soup was said to resemble clouds floating in the universe which is probably why its Cantonese name was wonton 云吞, meaning “swallowing clouds”.[5] Further evidence of wontons in the Tang dynasty reveals dehydrated wonton being unearthed from tombs dating to the Tang dynasty at Astana Cemetery, Xinjiang, China in 1959.[6] This shows the extensive influence of eating wontons, covering both the Northern and Western part of China.

Shu Xi ‘s Rhapsody on Pasta in Western Jin is another significant source on the history of wontons. Shu Xi uses laowan 牢丸 in his poem, which Knechtges theorises as the predecessor to wonton and jiaozi.[7] The skin of laowan was made with flour, stuffed with either minced pork or mutton and boiled in meat stock. Perhaps why mutton fillings never took precedence in Guangdong was because Southerners were repulsed by the smell of mutton.[8] During the Qing dynasty, wonton became highly popular and was eaten by both the royalty and general populace.[9] Although the meat fillings were usually pork, shrimp became more common due to Hong Kong’s coastal location when wonton noodle was brought over to Hong Kong from Guangzhou during the exodus of Mainland Chinese into Hong Kong in the 1940s and 1950s.[10]

Yang Xiong’s Fangyan also calls huntun as tang bing 汤饼 (boiled pasta/noodles) which is stuffed bing boiled in broth.[11] Questions have arisen on whether tang bing gave rise to noodles (mien) today which is interesting because mien and tang bing were both made from wheat flour and prepared by boiling them.[12]

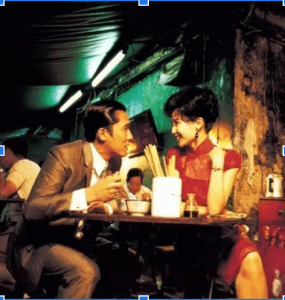

In Hong Kong, wonton noodles were first mass sold by street hawkers in the 1940s to 1960s which was a popular outlet to obtain food in a newly developing economy. They were sold in small bowls (sai yung) because wonton noodles were historically eaten as a snack rather than a full meal.[13] In popular culture, wonton noodles got so popular that it was even a term to describe directors in the 1950s who were lazy and uncommitted in their work.[14] It was said that these directors simply came in and quickly left to eat wonton noodles. They only came back when it was time to end the filming, earning the term “wonton noodle” directors. In the 2000 movie In the Mood for Love by Wong Kar-wai, set in ‘60s Hong Kong, one of the most significant scenes had the characters played by Maggie Cheung and Tony Leung pass by each other to have wonton noodles at a hawker stall.[15] Hence, one of the revealing ways to see how pervasive wonton noodles have developed in Hong Kong’s culture is to look into popular culture and in this case, it seems as though wonton noodles have become synonymous with the Hong Kong identity much like their yum cha culture.

[1] Liu, Junhui. 劉君惠, “Di yi pian: yang xiong yu ta de fang yan,” 第一篇:杨雄与他的方言 (Yang Xiong and His Fangyan) in Yang Xiong Fang Yan Yan Jiu 杨雄方言研究, First edition, Chengdu: Bai Shu Shu She 成都: 巴蜀書社, 1992, pp 75. http://img.chinamaxx.net.remotexs.ntu.edu.sg

[2] Knechtges, David R., “Gradually Entering The Realm of Delight: Food and Drink in Early Medieval China,” Journal of the American Oriental Society 117, no. 2 (1997): pp 234. https://www.jstor.org/stable/605487

[3] Mair, Victor H., Introduction and Notes for a Complete Translation of the Chuang Tzu, Sino-Platonic Papers 48, University of Pennsylvania, 1994, pp 24. http://sino-platonic.org/complete/spp048_chuangtzu_zhuangzi.pdf

[4] Girardot, Norman. J., Myth and Meaning in Early Taoism: The Theme of Chaos (Hun-tun), California: University of California Pressk, 1983, pp 29–38.

[5] Huang, Hsing-Tsung., “Food Processing and Preservation,” in Joseph Needham’s Science and Civilisation in China: Volume 6, Biology and Biological Technology, Part 5: Fermentations and Food Science, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000, pp 478–480.

[6] Huang, “Food Processing and Preservation,” 478.

[7] Knechtges, David R., “Dietary Habits: Shu Xi’s Rhapsody on Pasta,”. Early Medieval China: A Sourcebook, edited by Wendy Swartz, Robert Ford Campany, Yang Lu, and Jessey J. C. Choo. New York: Columbia University Press, 2014, pp 451. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7312/swar15986

[8] Knechtges, “Gradually Entering The Realm of Delight: Food and Drink in Early Medieval China,” pp 236.

[9] Zhao, Rongguang., “Culture of Food Made from Wheat,” in A History of Food Culture in China, Translated by Gangliu Wang and Aimee Yiran Wang, Shanghai: SCPG Publishing Publication, 2015, 36–40. https://doi.org/10.1142/z008

[10] Cheung, Sidney C. H., “Food and Cuisine in a Changing Society: Hong Kong,” in The Globalisation of Chinese Food, Hawaii: University of Hawaii Press, 2002, pp 103.

[11] Yang, Xiong 杨雄, Guo Pu 郭璞, and Cheng Rong 程榮. Fang yan : shi san juan 方言十三卷 (Fangyan: 13th volume), Shanghai: Han fen lou 上海 : 涵芬樓, 1421. http://img.chinamaxx.net.remotexs.ntu.edu.sg

[12] Huang, “Food Processing and Preservation,” pp 480.

[13] Huang, “Food Processing and Preservation,” pp 480.

[14] Chang, Jing Jing., “Towards a Local Community: Colonial Politics and Postwar Colonial Cinema,” PhD thesis, University of Illinois, 2011, pp 83–84. http://hdl.handle.net/2142/24192

[15] Wong, Kar-Wai, director, In the Mood for Love, 2000, Hong Kong, Criterion Collection, 2016, DVD.