The process of coral bleaching appears horrifying. Imagine an entire plain of multicoloured coral turning ghostly white all at once. According to the National Geographic (2010), the Caribbean has lost around 90 percent of its coral reefs, with half of all the corals lost due to bleaching (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, 2014).

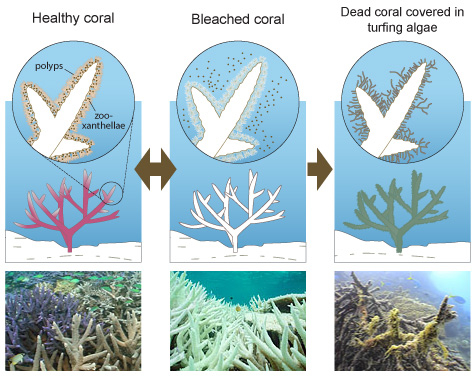

“When corals are stressed by changes in conditions such as temperature, light, or nutrients, they expel the symbiotic algae living in their tissues, causing them to turn completely white.”

– National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, National Ocean Service, ‘What is coral bleaching?’ –

The actual process of bleaching, however alarming in the way it makes coral change so drastically, does not actually kill the coral, as the definition by NOAA above states.

Coral bleaching occurs naturally when environmental conditions change, such as an increase in water temperatures (National Geographic, 2010). Like an aircraft forced to dump excess weight in an emergency, coral polyps evacuate the symbiotic zooxanthellae that live inside them. The measure does seem extreme, but there is evidence to suggest that bleaching could be a sly way of ensuring the coral’s own survival in the long run: by expelling algae that will not be able to withstand whatever environmental changes that elicited the bleaching, the coral make room for algae that could be more hardy than their previous zooxanthellae residents (National Geographic, 2010). Although the process is geared to help the coral survive, it it does make the coral more vulnerable to perishing (NOAA, 2014), along with ridding it of the colourful, life-giving zooxanthellae that reside in the coral polyps and provide energy for the coral through photosynthesis.

With human-driven climate change showing no signs of stopping, it is expected that coral bleaching will continue at an increasingly unhealthy rate. And to make matters worse for the coral of the Great Barrier Reef and other reefs around the world, another threat looms large: the crown of thorns starfish.

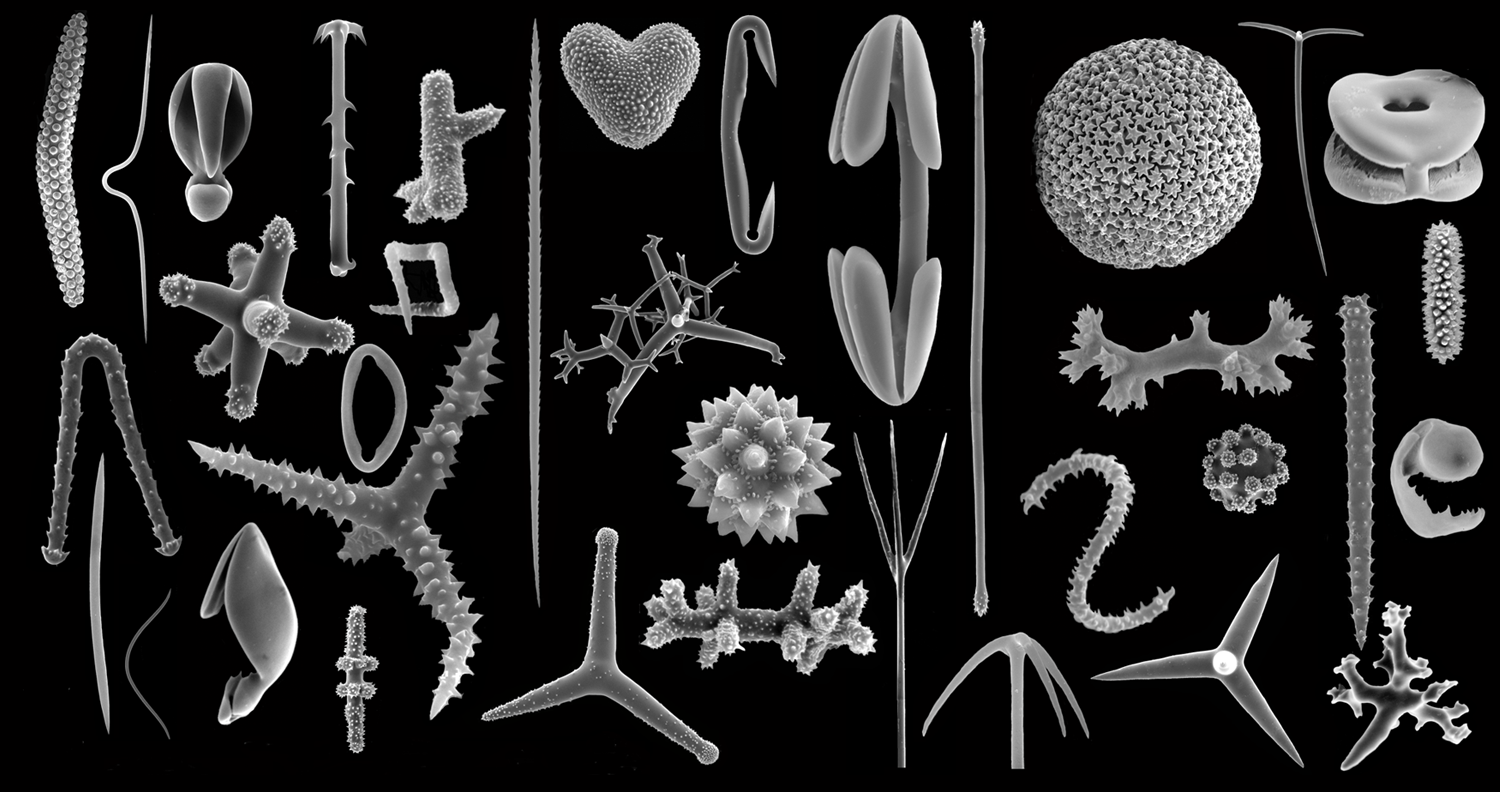

The menacing-looking crown of thorns starfish (or COTS, for short), unlike coral bleaching, really is as scary as it looks, and it is obvious from the first glance how the COTS got its name. The COTS is a large species of starfish, often reaching sizes of up to a full metre across, armed with anything from 7 to 23 arms bristling with venomous spines.

The COTS also has very few natural predators once it has reached maturity (although it probably has some of the weirdest predators, such as the Starry Pufferfish and the Triton’s Trumpet snail, seen devouring a COTS here). COTS larva, on the other hand, are more vulnerable to being consumed by a wider range of aquatic life, anything from crustaceans to fish (ARKive, n.d.).

Seemingly to counter this, female COTS can carry up to 60 million eggs at once (ARKive, n.d.). Multiple starfish also coordinate their spawning (just like coral do) to increase reproductive success. COTS populations can also see sudden growth spurts known as outbreaks. The sheer number of eggs one female carries means that even small populations of starfish can quickly repopulate and far exceed their previous numbers and spells disaster for coral. (ARKive, n.d.)

COTS outbreaks have been naturally occurring on the Great Barrier Reef every so often (Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, n.d.). However, once again due to human-related factors, a natural process now runs rampant and out of control. As with eutrophication (discussed in the post immediately prior), COTS outbreaks are affected by nutrients in the water. A study on the decline of coral cover in the Great Barrier Reef conducted by De’ath, Fabricius, Sweatman and Puotinen (2012) states that “water quality affects the frequency of COTS outbreaks in the central and southern GBR (Great Barrier Reef)”. What these scientists found is that nutrient-rich waters facilitated the growth of phytoplankton, which the larva of COTS feed and thrive on. Coupled with the already impressive reproductive capabilities of the starfish and the increasing frequency of outbreaks (De’ath et al., 2012), and it is clear that human activity is worsening the situation for the Reef.