Contents

1. Defining Language Standardisation

The confluence of diverse cultures and perspectives within a territory serves as one explanation for the evolution of language. This cultural evolution gives rise to an interesting phenomenon known as ‘language standardisation’. What is language standardisation? It is an ongoing historical process that develops a standard written and oral language to be practiced by everyone in a society. Primarily concerned with the evolution of specific human languages, standardisation can only occur when a society has an existing cultivation of their own language and communicative methods. Following, the society must then express a desire for uniformity by filtering out any irregularities and establishing a consistent communication system between individuals.

The process of standardisation involves both ‘ruler-makers’ and ‘rule-breakers’; the former makes the rules for spelling and pronunciation, in addition to selecting/eliminating the meaning of commonly used words. The latter, in contrast, are then stigmatized for using non-standard dialects. For instance, the use of double negatives – ‘that won’t do you no good’ – is deemed confusing, redundant and incorrect by the masses. Thus, keep in mind that language standardisation is a conscious course of development that produces both good and bad effects. Although standardising language may improve efficiency for the general population, there will be some who fall short of this new-found utility.

James and Lesley Milroy expressed that language standardisation does not symbolise an actual end-product, but rather, a significant process with no completion. They further noted:

“…it seems appropriate to speak more abstractly of standardisation as an ideology, and a standard language as an idea in the mind rather than a reality—a set of abstract norms to which actual usage may conform to a greater or lesser extent.” (p. 19)

Thus, we should remember that language standardisation is a process aimed at creating one standard, cohesive language in a society, although (due to the dynamic nature of society) it generally does not achieve this goal.

2. Stages of Language Standardisation

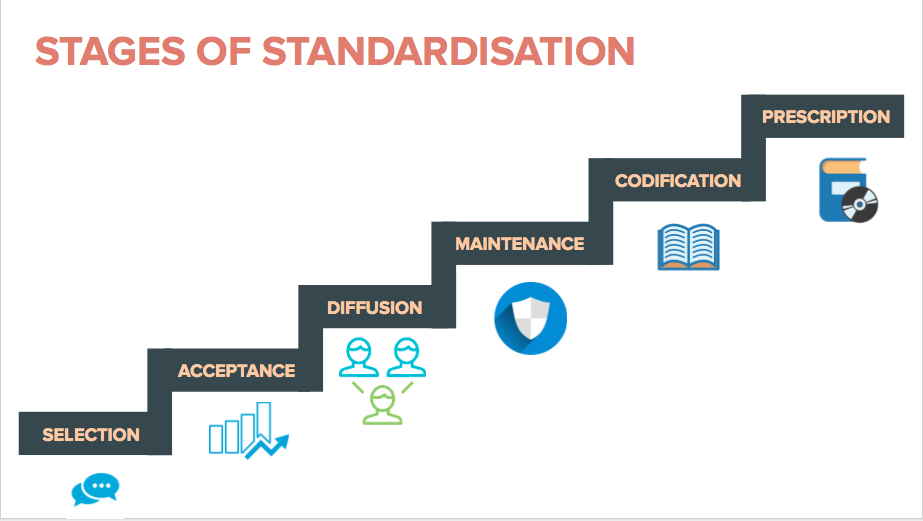

Language standardisation begins by selecting one of the many forms of language that exist in a society to be the standard. The chosen one is then accepted by the dominant clans in society, who have the power to control how and where this language is standardized and diffused. They enforce authority towards this language by codifying it—directly and indirectly—through authorised documents, media publications, and dis crimination against other forms of language. Once it has gained general approval, the standard language is rigorously maintained through several means. The first is an elaboration of function, where people of higher social standing perceive this language form to be more valuable and important than other variations. Secondly, the language then gains prestige within the society for being associated with those of high social status. Lastly, a writing system is established to prescribe this language (along with official dictionaries and guidebooks). Such system is then regarded as the absolute legitimate and “correct” standard of language, and hence, is esteemed above everyday speakers of the language.

crimination against other forms of language. Once it has gained general approval, the standard language is rigorously maintained through several means. The first is an elaboration of function, where people of higher social standing perceive this language form to be more valuable and important than other variations. Secondly, the language then gains prestige within the society for being associated with those of high social status. Lastly, a writing system is established to prescribe this language (along with official dictionaries and guidebooks). Such system is then regarded as the absolute legitimate and “correct” standard of language, and hence, is esteemed above everyday speakers of the language.

Those whom have accepted and are familiarised with the standard language can engage in discourse (Deumert 2), so to generate knowledge about communicative methods and processes. Establishing a standard language ultimately shapes the standard ‘reality’ of the people (Fairclough 203-4). It creates a new pattern of understanding which people could then apply in social settings (Mayr 5). Thus, those who refuse or cannot acquire the standard language properly are marginalised in the society, further widening the language gap. Overall, the whole process aims to create a ‘melting pot’ environment, homogenising a certain culture that comes with the language. It is important to note that these stages are hypothetical, and can sometimes overlap with one another. For instance, the maintenance stage can start quite early in the process, and continues throughout (Milroy 23).

3. Motivations for Standardisation

What motivations were there for language standardisation? For one, it was the Industrial Revolution – a period of great social, political, and economical change in Great Britain.

The growth in industrial technologies signified a great deal of cooperation between individuals of different skillsets, and effective collaboration could only occur when both parties speak and write the same standard language. With increasing literacy rates to match this language demand, citizens could advance from primary to secondary level, manufacturing-related occupations.

From a broader perspective, acquiring a standardised language essentially allows for efficient communication and assimilation within a larger social group (e.g. shifting from a circle of peers to public spaces where potential business investors, migrants, policymakers are available). Such networks proved particularly important for innovations requiring collaboration. Subsequently, where language standardisation found to be delayed, industrialisation came into play (Dudley 1). Unsurprisingly, literacy is still highly regarded today as the leading institutional marker for a nation’s development. With that perspective, we shall move to a unique, nation-wide territory where smaller-scale language standardisation took place: Basque Country.

4. The Language of Basque

The language of Basque is a language form derived from Basque Country. Located in northern Spain, the community saw themselves as autonomous given their diverse historical roots and cultural groups within the country. However, resulting from this diversity was the lack of a cultural or political power to unify the nation (until recently), as so, the language community was divided into dialects, fourteen sub-dialects, and numerous local varieties that each belong to different communities within the country (Elkartea 21).

The concern surrounding language variation dates back to the 16th century, where the first attempt for language standardisation was made. Instead of appointing one language form as the standard, Joanes Leizarrage developed a new language – one that was a combination of the various dialects he observed – that he believed would be understood by the general population (Elkartea 25). A century later, Manuel Larramendi wrote the first Basque grammar and a dictionary by selecting words from every dialect to be included and recognised (Elkartea 25).

Fast-forwarding to the nineteenth century, the people pf Basque expressed an increasing desire to preserve the nation’s language culture with all its diversities. Hence in 1919, a Basque Language Academy, Euskaltzaindia, was established with the primary aim of formulating a standardwritten language. The basic objectives of the academy were:

- To regulate the use of Basque spelling and lexicon

- To contribute to the creation of a language that will be valid for all parts of Basque

(Elkartea 28)

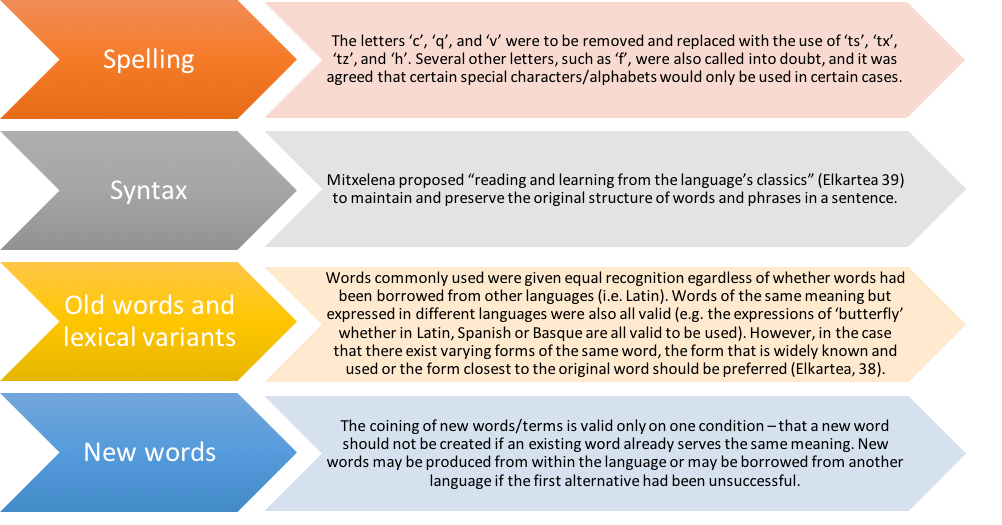

In a further effort to standardise the language of the country, Koldo Mitxelena proposed a set of guidelines for the new language standard in 1968. He had stressed on the fact that “Basque should move towards unification, and unification should commence chiefly with matters of form” (Elkartea 36). First, he nominated the central dialect as the standard language of the country as he believed it to be “where the heart of [the] country is, and because it has played a dynamic role in the history of [their] literature” (Elkartea 32). Second, he then proposed the following series of changes:

Unfortunately, Mitxelena’s proposals were not met with instant consent. Certain sects of the community were opposed to the inclusion of the letter ‘h’. Particularly the older, conservative delegates believed it to be a pointless addition of an alphabet that could not be pronounced (Elkartea 34). However, as the use of ‘h’ were valued by the northern Basque writers and speakers, Mitxelena saw the importance of its inclusion in the standard language. The intentionality of reforming the spelling was not to simply standardise the language but to also unify all Basque under a common understanding.

In the end, Mitxelena reasoned that “the young are always right” (Elkartea 36), and since the young writers were in favour of the letter ‘h’, the spelling reformation was ruled. It was no doubt a sensible decision as the younger generation of writers, speakers, language educators etc. would be the ones to spread the use of this standard language.

Ten years after the proposal was passed, efforts to implement the standard language was assessed and the results were as follow:

- Among, 431 publications made between 1967 and 1977, only 3.3% of books published in 1967 had incorporated the new rules of spelling, declined and conjugated forms. However, in 1977, almost 65.4% of publications complied with the standard guidelines.

- 90% of 570 language educators used the standard language daily (viz. in aspects of writing, reading, and speaking), while 80% agreed that learning and using the standard Basque was necessary for work and for everyday life.

- Language educators were also deeply motivated to teach the standard Basque. They believed that the promotion of the standard was “essential to turn Basque into a modern instrument”

- 61% of the 196 Basque writers that were interviewed used the standard language in their writings for they believed in the “need to convert the language into an instrument of culture”

(Elkartea 44-45)

In overall, it is evident that the majority believed in the good of a standardised language in Basque. The Basque case study is significant not only for the fact that it is relatively recent but that it also reflects Milroy & Milroy’s conception that a language standard is not an end-product to be achieved, but rather, it is a process of development that the society embarks on. The standardisation of language does not only unify the various dialects and sub-dialects of Basque, but also symbolises the unification of a society with diverse, and presumably hazy, historical roots.

5. Implications and Clarifications

One point to note is that human language does not necessarily need to divide into different forms. Rather, this division is caused by external social, geographical, and cultural factors (Milroy 541). Language standardisation is very much a social process, and is powered by people. Societies themselves pick their own standard forms of language, and hence, different societies in different places, and of different cultures, can all pick vastly different (or even somewhat similar) language forms to adhere to. Hence, we can see that this division is somewhat “man-made”. It is the choices societies make that result in differing languages. Hence, the dispersal of a language must be credited to its respective speakers—people, and their practices and customs—and not the core of language itself.

Additionally, we must recognise that language standardisation also ensues in response to increasing trade and capitalism. Development in these areas create pressure to establish regularity in other areas, such as currency and language, to facilitate and increase efficiency in communication between countries. Thus, we can see that language standardisation is not only concerned with linguistic and literary goals, but also largely fuelled by economics, trade, and enterprise (Milroy 534-535).

Another interesting point relates to the superiority of specific language forms. Some might feel that the standard form of a society was chosen because it is superior to all other options. However, this ‘superiority’ may be a social construct, attributed to certain language forms because of the social standing of their speakers (Milroy 532). Language varieties gain prestige when its speakers possess high social standing. If a language form is used by the upper class, society automatically esteems it over other forms and views it as the supreme option, even though it does not necessarily allow us to communicate or express ourselves better than other forms. Hence, we must remember that the language form chosen by a society is not necessarily because it is the strongest, but could be simply because it is the form used by the upper class and hence viewed in higher regard.

Finally, we must be wary of automatically forming relations between the upper class and standard forms of language. Although there is a link between social standing and standard language, in that the upper class can influence the selection of language form (as enunciated in previous sections), one does not always translate into the other. One example of this is British Received Pronunciation, which some scholars deem the ‘standard’ form of English in the United Kingdom (Milroy 532-533). Despite being associated with the upper class and being well-educated, most recent reports suggest that this form is practiced by a mere 2% of the population (British Library Board). Therefore, it is evident that it does not represent the consensus of the United Kingdom. Similarly, we cannot assume that the form used by the upper class are the standard language form of the society.

6. Concluding Notes

Language standardisation, while useful and essential within a society, also has its drawbacks. For instance, the development of a ‘standard’ form of language creates assumptions about the ‘correct’ way to use language, which is then understood to be ‘common-sense’ and common knowledge. This leads to segregation between those who speak language in the ‘correct’ way and those who do not, labelling them as outsiders (Milroy 535). Furthermore, it creates a sort of ignorance towards other dialects and ways of speaking. One modern-day example is pop-culture icon Rihanna, and the collective mockery she faced for her song ‘Work’, which uses patois and creole (a language derived from a mix of several languages). Unaware of the existence of such slang, fans and music critics alike were quick to deem the song complete ‘gibberish’, despite its lyrics possessing proper meaning and semantics (Thomas). Thus, it is crucial to understand that the standard language forms are not universal, and they can still have varieties across different regions. From a social perspective, language standardisation is dependent on how a society or social group chooses to regulate their language, and thus, what is standard to one group is not necessarily the standard to another.

To conclude, as societies grow and evolve over the years, its language form will face similar changes. As such, standard forms of language can differ at different points in time, even within the same society. This essentially re-emphasises that language standardisation is a process, not an end-result. With every generation, new words are constantly invented and introduced into the language lexicon, which may then be taught to the next generation (Crystal 132). Therefore, language standardisation is never stagnant or complete, but will continue revising itself as long as the language is still in use.

Bibliography

British Library Board. Received Pronunciation. British Library, n.d.,

http://www.bl.uk/learning/langlit/sounds/find-out-more/received-pronunciation/. Accessed 1 April 2017.

Crystal, David. A Little Book of Language. Yale University Press, 2010.

Deumert, Ana. Language standardisation and language change: The dynamics of Cape Dutch.

Vol. 19. John Benjamins Publishing, 2004.

Dudley, Leon. Getting It: Language standardisation and the Industrial Revolution. WordPress, 9

March 2015, Dudleylm.files.wordpress.com. Accessed 6 March 2017.

Elkartea, Garabide. Language Standardisation:Basque Recovery II. 2010.

Fairclough, Norman. “Political correctness’: The politics of culture and language.” Discourse &

Society 14.1. 2003.

Leith, Dick. A social history of English. Psychology Press, 1997.

Mayr, Andrea. Language and power: An introduction to institutional discourse. A&C Black,

2008.

Milroy, James and Lesley Milroy. Authority In Language. Routledge, 2000.

Milroy, James. “Language Ideologies and the Consequences of Standardisation”. Journal of

Sociolinguistics 5/4 (530-555), 2001

Thomas, Tiffany. Rihanna’s ‘Work’ Lyrics Use Creole & Patois, Totally Confusing Music

Critics. Romper, 25 March 2016, https://www.romper.com/p/rihannas-work-lyrics-use-creole-patois-totally-confusing-music-critics-7707. Accessed 10 March 2017.