Body, Mind and Soul in Second Language Acquisition

This page seeks to break down the impact of the body and the mind on second language acquisition. The impact of the body is broken down into the visual as well as the gestural. The impact of the mind will be understood first by understanding current theories on how the mind interacts with language in the bilingual mind and then later will go on to explain the impact of the actions on the body, on the mind and how that affect second language teaching methods.

GESTURAL LEARNING

Speech can be expressed in a three-dimensional method, namely body language. Body Language takes the definition of different forms of non-verbal communication. Through body language, the speaker is able to express his or her feelings and intentions through bodily behavior, which encompass body posture, gestures, facial expression and eye movements. Just a simple example would be the action of someone enjoying a spread of food. Their eyes would be wide opened and their body posture would reflect enthusiasm. The speed at which they swallow their food will be fast too. This actually depends on the culture too. Since body language is culture specific, different cultures have got different way of expressing themselves. In Japanese culture, slurping a soup loudly shows that the diner is praising the chef’s cooking, while in English culture, eating noisily implies being disrespectful. With this, we can see how actions are able to reflect one’s mood, besides portraying direction and displacement. It has been proven that gestures aids comprehension of a foreign language. The gestures can be further disembodied into congruent and incongruent gestures.

CONGRUENT GESTURES

Hand Gestures

Congruent gesture, also known as co-speech gesture, involves either verbal or non-verbal communication with hand and body movements at a very deep semantic level. According to McNeill (1992), iconic gestures are natural and prevalent aspects of spoken language which are not arbitrary. At the same time, it brings across informations that visually refer to the concept that it suppose to convey. These gestures can be iconic, like drinking water requires the speaker to raise his thumb to his lips with the pinky out and tilting the head backwards. When speaking, one will unconsciously make prominent gestures, which gets registered into the listener’s head; learnt and remembered with the linked gesture. These iconic gestures are useful inputs to learners of a second language during comprehension and learning (Kelly et. al, 2009). We can see that congruent gestures are associated with meaning of the speech. The association produces stronger and more multimodal memory representations as it incorporates the use of gestures and also speech.

Lip Reading

Other than that, lip reading is also classified under congruent speech, and is one out of the many aspects of speech. Lip reading and hand gestures would be applicable when differentiating the length of syllables and vowels. The beats made by the hands and the movement of lips can be put together to make out the length of the particular syllable. When the speaker is trying to recall back the word, the impact of the hand gestures somehow makes the semantic recalling process easier and faster, besides ensuring the word pronunciation is accurate. This multimodal information combined with speech helps listeners to comprehend language better(Clark, 1996; Goldin-Meadow, 2003; McNeill,1992).

NCONGRUENT GESTURES

Under incongruent gestures, basically the bodily movements made are not consistent, whereby for the same word said, the gestures keeps changing. Despite the repetition of the words, it does not get registered into the brain of the second language learner because every time, the gestures changes. For instance, someone saying hop and making the action of a peace sign going up and down; just like re-enacting a rabbit’s movement. In other cases, the person might make gestures imitating a kangaroo’s hop. Both actions made were inconsistent. Consequentially, the learners are not able to retrieve the information easily from their memory when it is being said the next time round, especially when it . The mismatch of speech and gesture causes some kind of confusion in the brain and thus when trying to recall the words, it would be harder to retrieve it. In Kelly et. al. (2009) research on the Japanese language, words encoded with consistent gestures were better memorised as compared to the incongruent ones.

HOW AND WHY IS MEMORY ENHANCED BY GESTURES?

According to Zimmer et al.(2000), not just the wordbank of the learner is expanded, but how long the word is retained in the brain is also lengthened. To add on, the enactments allows the effortless accessibility and retrieval of these words in the long run. Thus, it aids in the retainment of the new words learnt for future uses as these words get conceptually linked with the learner’s first language.

EFFECTS OF GESTURAL LEARNING ON SECOND LANGUAGE ACQUISITION

Despite at times the gestures are not related to the meaning of the word, the fact that the gestures are enough to make the second language learner remember the word and meaning is imminent. However, on the contrary, it only works for the case of congruent gestures and not for incongruent gestures. Besides that, sometimes, the hand movements and body movements might be too much of visual information, which makes it distracting for the learner to capture the meaning of the word. Generally, the input from speech and gestures facilitates second language learning only up to the semantic level and not the concept.

With this, we come to question if this method is applicable for the use of learning any second language. As stated above, languages are culture specific, be it sign language or just language, this means that different cultures have got different interpretations of different gestures. For instance, the Okay or OK sign is mostly considered as a good hand gesture. The hand gesture is used by curling the index finger over the thumb and the remaining fingers extended above them. This means that everything is good or well. Also, this sign is usually used by divers to indicate all is well or OK as the thumbs up sign means ascending. However, in Latin America and France it is considered as an insulting sign as it is thought to mean your anus and has negative connotations attached to it. In Australia, it means zero and in Germany it may mean a job well done or an offensive insult depending on the region you visit. In New Zealand, this sign is not used much and considered a cheap way of saying OK. In Turkey, the OK sign means one is a homosexual.

Even so, gestures are still useful for second langugae learners because they aid social interaction by streamlining action understanding between speakers besides improving language comprehension. According to Oztop, Wolpert and Kawato (2005), the imitative motor helps listeners anticipate other people’s actions better by genereting forward models. With this, gestures are important in aiding a person when learning a new language.

VISUAL VS AUDIO LEARNING

VISUAL LEARNING

Lip Reading

Lip reading, sometimes known also as speechreading, is a means of understanding speech visually. It is described as “seeing the sound of speech” because the lip reader relies on observations of the speaker’s lips, mouth and tongue to interpret speech. (Short et. al, 2012) It is a technique primarily used by individuals who are deaf or hard of hearing. Even without the absence of auditory ability, lip reading has shown to be an integral part in conversations in everyday life. People with normally-functioning audio and visual skills tacitly use lip reading to understand speech. Using lip reading allows one to enhance or quicken his understanding of what is being said by observing the syllables of each word, rhythmic patterns and phrases which are articulated by the speaker through the movement of his lips. Each phoneme in speech has a corresponding viseme (facial or mouth position). In general, people are able to identify a phoneme in the absence of audio cues, by paying close attention to the visual cues given. In any given language, lip reading alone is able to capture around 40-60% phonemes. (Schwartz et. al, 2010)

Words Have Images

It was first proposed by Engelkamp & Krumnacker (1980) that the gesture accompanying a particular word is linked to an image which already exists in the semantic inventory of the word. Through years of experimentation, neuroscientists and linguists have discovered the extent of the connection between the human body’s linguistic and motor systems, following the assumption that in every language, words have images associated with them. This accounts for the effectiveness in employing meaningful gestures to accompany words when teaching a foreign language. More on the neurological aspect of visual learning and word imagery may be found under the section on ‘impact of gestures on the Brain’

AUDIO LEARNING

Imitation

Imitation in language involves numerous behaviors, namely speech patterns, gestures, facial expressions and mannerisms of the imitatee. It is an important element of social interaction which allows speakers to feel a greater sense of relatability and empathy. Imitation of speech patterns, in particular, are of interest in the field of second language acquisition as it gives evidence that auditory exposure is likely to be beneficial by aiding comprehension and speech production in a nonnative language.

A recent study conducted by Adank et. al (2010) has shed light on vocal imitation and its effect on spoken-language comprehension. Participants (all of whom were monolingual speakers of Dutch from the Netherlands) were exposed to training in an unfamiliar, novel accent of Dutch, and given a pretest to assess their comprehensive ability of the novel accent. They were then divided into 6 different groups which received either no training or different forms of training in the accent, after which they were given another comprehension test to assess their ability post-training. The results of the test have shown that the most effective means of improving comprehension was when participants underwent training which required them to imitate the pronunciation of words in the novel accent. Therefore, it can be said that in the acquisition of a nonnative language, imitating speech patterns of that language allows the learner to create better associations for particular words, which makes him quicker to anticipate these words in speech and in doing so improve his understanding of the language.

EFFECTS OF VISUAL AND AUDIO LEARNING ON SECOND LANGUAGE ACQUISITION

Given the mostly positive effects that both visual and audio learning have on learning a nonnative language, there are now questions to how either form of learning may influence the other, if both are combined.

Based on numerous studies which have found adults’ nonnative language comprehension to improve (though not to native level) through auditory training, Hirata & Kelly (2010) investigated the effect of visual information on auditory ability.

In their study, 60 participants, all monolingual speakers of English, first sat for a prettest and were then given 4 different types of training in Japanese- audio-only, audio-mouth, audio-hands, and a combination of audio, mouth and hand gestures. The results of the posttest proved insightful- it seems that lipreading was more effective in facilitating phoneme learning rather than beat gestures.

While gestures are semantically significant in second language acquisition, they do not contribute effectively when functioning in a phonological aspect. That is, only congruent gestures would aid in one’s understanding of a nonnative word because they carry the meaning of the word, but beat gestures on the other hand carry no meaning in themselves but are used for rhythmic emphasis.

It is interesting to note as well that two channels (audio-mouth, audio-hands) of information during the training were more effective than when three channels were used. Though this may be surprising, it is likely due to an “overload” in participants’ working memory in which they are unable to encode the audio information properly because their attention is shared between the visual and audio learning cues in addition to the audio provided.

The findings from Hirata & Kelly’s study, coupled with previous studies on auditory and visual learning that have been conducted over the past few decades, have implications on possible methods that will be developed to aid in second language acquisition.

THE MIND AND SECOND LANGUAGE LEARNING

This section will discuss the more popular theories and models used by linguists to understand the way a bilingual mind stores and sorts language.

HOW THE BRAIN REPRESENTS TWO LANGUAGES

Concept Mediation Model VS Word Association Model

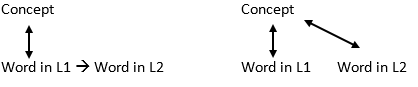

These two models were proposed by Potter et al in 1984.

The Word Association Model (WAM) suggests that the lexicon of the L1 is linked to a concept but the lexicon of the L2 is linked to the lexicon of the L1, not the concept. So an L2 learner would simply think of the word in the L1 and then connect it to the word in the L2. No other processing takes place.

Concept Mediation Model (CMM) on the other hand believes otherwise. The focus on this model is on conceptual understanding. This model believes that the lexicon of both languages are linked through concepts. Hence when a L2 learner wishes to retrieve a word in the L2, they think of it in the L1, then relate it to the concept and the concept relates back to the word in the L2.

Here is the WAM and CMM models visually:

Reversed Hierarchical Model

The Revised Hierarchical Model (RHM) is another model of mental representation in the bilingual mind. It is the revised model by Kroll & Stewart in 1994 and combines both aspects of the CMM and WAM. The RHM believes that in the initial stages of L2 acquisition, the brain uses the WAM as learners in L2 classrooms tend to learn new words by comparing it against the lexicon of their L1. However as their proficiency of the L2 increases, the brain evolves and they begin to use the CMM to store the lexicon. This is particularly useful when more experienced L2 learners come across expressions that do not exist in their L1. The CMM allows them to store these by developing new concepts. These concepts include grammar as the grammar system of an L1 and L2 may be different and translating word for word in such cases would result in ineffective communication.

Shared Memory Theory VS Memory Independence Theory

In discussing these two theories, the distinction between two categories of bilinguals is important; Compound Bilinguals and Coordinate Bilinguals. Compound Bilinguals are defined as bilinguals who learn two language in the same context where they are used concurrently. This can be from birth, in bilingual household, and can also be bilinguals coming from a bilingual education system where there is a focus on both languages such as immersion programs. Coordinate bilinguals are defined as Learning two languages in 2 different environments that never overlap. These refer mostly to older learners who learn the L2 purely academically, and have little use for the language outside of the classroom.

The Shared Memory Theory and Memory Independence theory is another set of ways in which the brain handles languages. It is similar to the RHM as proficiency determines which theory a L2 learners mind is more adjusted to however they differ as well because the focus is not on how memory is retrieved as it was in the CMM or WAM (4.1.1) and RHM (4.1.2) but on how it is stored. In the Shared Memory Theory, compound bilinguals are more capable of alternating between their languages with ease as the theory believes both languages share a single memory store for both languages that enable them to work closely together. The Memory Independence hypotheses however believes that each language in the brain has its own individual memory systems. Thus the storage and operation of each language is independent. This hypotheses is associated most with coordinate bilinguals who tend to have difficulty code-switching.

HOW UNDERSTANDING THE MIND CAN IMPACT SECOND LANGUAGE ACQUISITION

In attempting to understand the process of how second language is acquired, it is obvious why studying how the brain functions when it comes to languages is so important. The brain is the main tool responsible for learning and acquisition. Without the brain, learning would not be possible. Hence it is important to understand the ways in which the mind handles, processes, and stores information. It is also important to study how other methods of learning impact the brain to see if these methods are worth exploring into further if we hope to improve current Second Language teaching methods.

OTHER THOUGHTS AND RELATED AREAS

This section of the blog attempts to conclude the information in other sections as well show an area of research in this field that was of interest to us.

The information that has been presented in this blog are all targeted at the different functions the body and mind play in second language acquisition. These various parts must all be viewed as interconnected. No one part can exist without effecting and being affected by the other parts. Thus the various implications that the research covered has on second language learning and how it may impact teaching methods depends very much on which components individuals choose to center their own focus on for either more research in laboratories or in practice in the classroom.

One area of interest in on the local front. The keen relationship the body and mind have with language acquisition is all the more significant, with Singapore’s racial and cultural diversity giving rise to a unique bilingual and even multilingual background not found in most other nations of the world. Traditionally, the time-on-task method of learning English through increased exposure was used, with English becoming the language of instruction for mathematics and science in the 1970s, instead of a mother tongue language (Chinese, Malay or Tamil). This however resulted in a decline in the science results of Chinese-medium students, proving that merely increasing the amount of time students received exposure in these languages was clearly not sufficient in enabling the students to have a better grasp of English as their L2. Instead, Dixon (2009) suggests that the quality of input in the target language should be emphasized on instead, and such high-quality input would include the use of “body motions” and “visual aids” among others, which would provide input which students will be able to comprehend during language learning. At present, the same concept can be applied when teaching the mother tongue languages (Chinese, Malay and Tamil) instead of encouraging students to learn by rote or the time-on-task method. With such an approach, young learners will be more engaged and develop a more positive attitude towards learning their mother tongue language.

References

Gestural Learning:

Hand gesture of differents cultures. (2013, April 14). Retrieved October 28, 2014, from http://www.slideshare.net/NirmalaPadmavat/hand-gesture-of-differents-cultures

Kelly, Spencer D., McDevitt, Tara and Esch, Megan, (2009). Brief training with co-speech gexture lends a hand to word learning in a foreign language. Language and Cognitive Processes, 24:2, 313-334

Oztop, E., Wolpert,D., & Kawato,M. (2005). Mental state inference using visual control parameters. Cognitive Brain Research, 2, 129-151.

Zimmer, H. D., T. Helstrup & J. Engelkamp, (2000). Pop-out into memory: A retrieval mechanism that is enhanced with the recall of subject-performed tasks. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning Memory and Cognition 26, 658–670.

Visual vs Audio Learning:

Adank, P., Hagoort, P., & Bekkering, H. (2010). Imitation improves language comprehension. Psychological science, 21(12), 1903-1909.

Dohen, M., Schwartz, J. L., & Bailly, G. (2010). Speech and face-to-face communication–An introduction. Speech Communication, 52(6), 477-480.

Engelkamp, J., & Krumnacker, H. (1980). Image-and motor-processes in the retention of verbal materials. Zeitschrift für Experimentelle und Angewandte Psychologie.

Hirata, Y., & Kelly, S. D. (2010). Effects of lips and hands on auditory learning of second-language speech sounds. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 53(2), 298-310.

Short, M., Murray, K., Cooper, A., Finlayson, M., Little, D. and Wickens, B. (2012). Lipreading, from http://www.lipreading.net/lipreading.htm

The Mind and Second Language Learning:

Kroll, J. F., & Stewart, E. (1994). Category interference in translation and picture naming: Evidence for asymmetric connections between bilingual memory representations. Journal of Memory and Language, 33, 149-174.

Nilsson, L. G., L. Nyberg, T. Klingberg, C. Aberg, J. Persson & P. E. Roland. 2000. Activity in motor areas while remembering action events. Neuroreport 11, 2199–2201.

Nyberg, L., K. M. Petersson, L. G. Nilsson, J. Sandblom, C. Aberg & M. Ingvar. 2001. Reactivation of motor brain areas during explicit memory for actions. Neuroimage 14, 521–528.

Potter, M. C., So, K-F. S., Von Eckardt, B., & Feldman, L. B. (1984). Lexical and conceptual representation in beginning and proficient bilinguals. Journal of Verbal Learning and Verbal Behavior, 23, 23-38.

Dixon, L. Q. (2009). Assumptions behind Singapore’s language-in-education policy: implications for language planning and second language acquisition.Language Policy, 8(2), 117-137.

First Created by Sathrin Kaur Saggi D/O Karamjit Singh, Valerie Teo Minyi, Nadzirah Binte Amir Hamzah, AY2014/15 Semester 1