Multisensory Nature of Speech: As humans, we like to maintain eye contact with the person we are engaged with in a conversation, and infants do this too! In fact, we are innately born with the tendency to understand the multisensory aspects of speech. Previous studies have shown that infants selectively direct their attention towards faces that are talking and often pay a lot of attention to the orofacial, or to the mouth and the face, of people they are socially attending to. These orofacial cues help infants to orient themselves to the speech they are hearing and learn how their native language works.

Bilingualism, according to some research, has an edge in helping infants attend to the visual aspects of speech. In a study by Birulés et al. (2018), 8- to 18-month-old bilingual infants express a greater interest in orofacial cues than monolingual peers. Complementary research also suggests that bilingual infants are more adept at telling different languages apart in a visual manner. So, children exposed to bilingual environments are more responsive to visible aspects of speech than monolingual children, but does this difference impact how they learn new words? What about other sensory modalities, such as auditory aspects of speech?

The Study: In a study conducted by Havy and Zesiger, 30-month-old bilingual children were tested on their capability in identifying new or novel words taught to them either auditorily or visually. This is called “lexical mapping”, in which a new word (e.g., ‘var’) is presented with either an auditory representation (hearing an audio recording of the pronunciation of ‘var’) or visual representation (seeing an object presented alongside a silent talking face pronouncing ‘var’). The children were then tested on their ability to identify the word (“Look at the ‘var’!”).

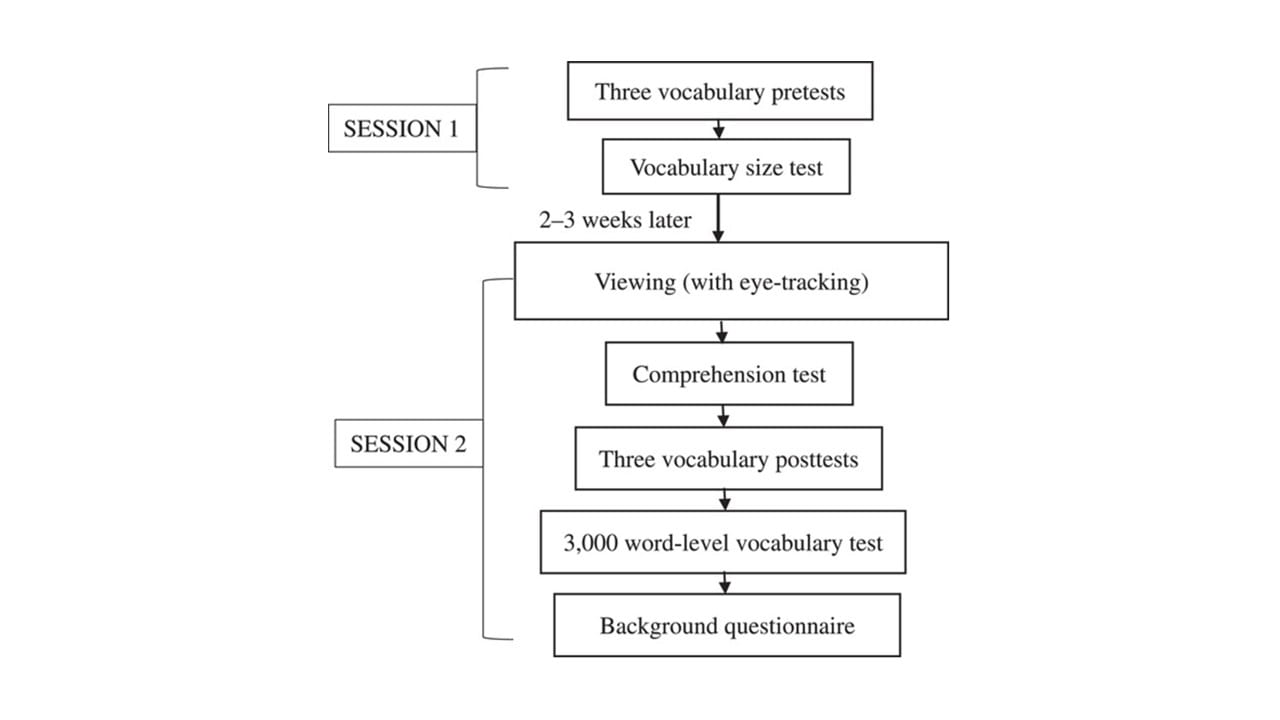

The bilingual children were first split into one of two learning conditions: either the auditory modality or the visual modality. Children from both modalities go through the familiarisation phase, where they hear a video recording of a person saying the novel word (‘var’). Then, in the learning phase, the children in the auditory modality group hear the new word and see a black screen, while the children in the visual modality group see a visual display of the new word (represented by an object on screen) and see the video recording from before, but in silence. In the testing phase, both the auditory and visual modality groups were tested for their ability to recognise the word, in both the same modality (auditory group presented with an auditory recording) and cross-modality (auditory group presented with a silent video visual recording).

Results: Findings from the study suggest that bilinguals are better at learning cross-modal representations of new words that were learned in a visual manner. This means that bilingual children are better able at recognising words spoken auditorily when they were previously only exposed to it visually than monolingual children are.

So, what does this all mean, and how does this relate to our Singaporean parents and children?

As a result of enhanced sensitivity to orofacial speech cues (or “hints” when we use our mouth and face), bilinguals are more confident in recognising representations in other modal forms. Perhaps a tip for our Singaporean parents is to exaggerate one’s facial features when speaking words that are difficult to grasp, to help our children better pick up the language (and perhaps try this in the less dominant language). Additionally, cross-modality testing for words can be a good test for how confident one is in the language.

This post was written by our intern, Shi Fan, and edited by our lab manager Fei Ting and Research Fellow Rui Qi.

Reference(s):

Birulés, J., Bosch, L., Brieke, R., Pons, F., & Lewkowicz, D. J. (2018). Inside bilingualism: Language background modulates selective attention to a talker’s mouth. Developmental Science, 22(3), e12755. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/desc.12755

Havy, & Zesiger, P. E. (2021). Bridging ears and eyes when learning spoken words: On the effects of bilingual experience at 30 months. Developmental Science, 24(1), e13002. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1111/desc.13002