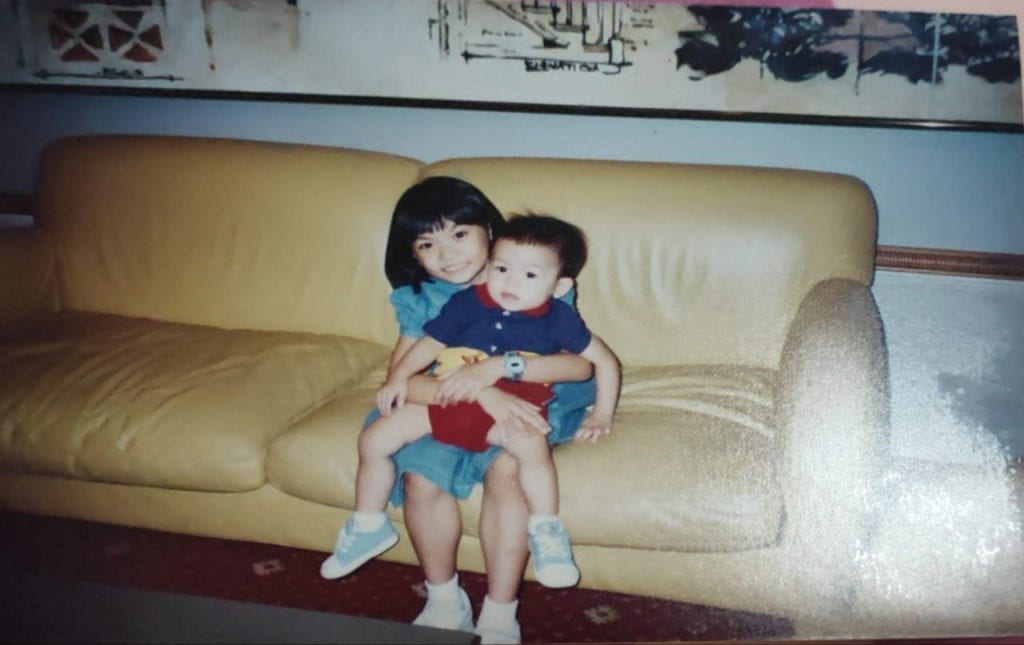

When I went to Boston for a few months as a child and came back to Singapore, people said my accent changed, but I didn’t think so. I couldn’t hear it myself, but I could feel that the way I was shaping my words was different. I could feel that my words were rounder than usual, and used more of the back of my mouth than I used to. My family noticed, and my friends teased me, but I was oblivious. I hadn’t learned it consciously, yet my tongue remembered. This unconscious mimicry made me fascinated about the unconscious mechanisms of child language learning, and leaves my adult self staring wistfully at my Duolingo notifications, wondering where that magic went.

As a child, I managed to learn Cantonese and Japanese alongside the prescribed Singaporean languages of Mandarin and English, but that facility seems to have since faded. I’ve been trying to learn Hindi for a few months, in order to communicate with my boyfriend’s relatives, and to say that it hasn’t been as easy as my childhood experiences is an understatement. The hardest thing to wrap my mind around has been the introduction to gendered nouns. It becomes even more confusing when one realises the gender of the noun is not carried on the noun itself, but on the accompanying noun modifiers. For example: “She is reading her book” in Hindi is “Vo apni kitab padh rahi hai” – the gender of the owner of the book is carried on the possessive (apni) and the present participle (rahi hai) but not on the pronoun itself (Vo). When I complain of the difficulty, I am met with sympathetic nods and people saying that they simply learn the sentential structure as part of the word when learning the language as children.

Which brings me back to the original question: what causes the unparallelled facility of children in learning languages, and is it possible to replicate it as an adult? The answer to the first part of the questions lies in a confluence of factors: a brain built for exploration, a playground of fearless communication, and the constant symphony of immersion.

The Brain’s Linguistic Jungle Gym: Picture a child’s brain as a vibrant jungle gym of neural pathways, buzzing with activity. Every sound, every interaction, builds new connections, a labyrinth where languages weave and intertwine. Unlike adults whose pathways are paved and settled, children have a brain under construction, a “critical period” where they effortlessly absorb sounds and rhythms, mimicking them with a near-native precision that eludes many adults. Even their vocal cords are more adaptable, morphing to new pronunciations with relative ease.

Fearless Explorers of Words: Probably the bigger issue boils down simply, to shame, which is no doubt more ingrained in adults than children. Even when meeting people who can speak Hindi, I am usually too shy to try, letting my long pauses and perceived awkwardness fill me with panic. By contrast, children approach language with the courage of explorers, unburdened by self-doubt or the pressure of “getting it right.” They babble, experiment, make mistakes without flinching, piecing together the puzzle of communication through trial and error. This playful approach allows them to focus on the fun, the music, the emotional connection, rather than the technicalities. Adults, burdened by the “work” of language learning, sometimes forget this essential element. When learning becomes a chore, rather than a playful exploration, the spark of curiosity dims, and the path to fluency becomes a dusty road.

So, what can I do to recapture the magic of childhood language acquisition? I guess the answer lies in embracing the child within. To immerse myself in the language. Find opportunities for playful interaction, conversation, and laughter. Embrace the mistakes, the stumbles, the silly pronunciations. And most importantly, let go of the pressure to be perfect.

I want to have faith that we can all become linguistic chameleons, and it may take more effort than it did for our younger selves, but I have to learn to see the journey itself as a reward. After all, my attempts to learn the Hindi language is not just about mastering grammar and vocabulary; it’s about finding out more about my boyfriend’s family’s culture, their perspectives, and world. Here’s hoping I can shed my doubts, and let myself go on a wonderful cultural odyssey.

Jin Yi is our Research Assistant, working on the language mixes project. Jin Yi’s languages are English, Mandarin, Cantonese, Japanese and Arabic.

Want to read more of our Multilingual Memories? Click here!