Have you ever been so focused on a task or activity to the point that you stopped noticing the passage of time, and even forgot to eat or drink? Like you’re just “in the zone” and feel a deep exhilaration or great enjoyment? I believe most of us have experienced this before. Or at least, I know I experienced this when I’m playing a game or reading.

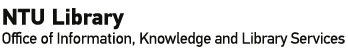

This state in which people are “so involved in an activity that nothing else seems to matter; the experience itself is so enjoyable that people will do it even at great cost, for the sheer sake of doing it” (p. 4), is called the flow state. This is the key discussion point in this classic and popular title in positive psychology, Flow: the psychology of optimal experience by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi.

The book starts with Csikszentmihalyi discussing the concept of happiness and defining it as “a condition that needs to be prepared for, cultivated, and defended privately by each person” (p. 3). It is a condition achieved by mastering control over the contents of our consciousness. The state of flow that we achieve by this mastery is as close as it gets to true happiness; this is when we are fully engaged, in complete control of ourselves regardless of the situation. He then discusses the mechanism of consciousness and how it can be controlled in chapter 2.

“People who learn to control inner experience will be able to determine the quality of their lives, which is as close as any of us can to being happy.”

In chapter 3, Csikszentmihalyi discusses the difference between pleasure and enjoyment. These two terms are often interchangeable, but he makes a clear distinction in this case: pleasure is a feeling of contentment that is achieved when social or biological expectations have been met, e.g. eating a meal when we are hungry is pleasant because we are fulfilling our biological needs. Enjoyment, on the other hand, is a feeling that occurs not only after the needs are met, but also when something else is achieved beyond expectations; it is characterized by a sense of novelty and accomplishment e.g. playing a game of chess that stretches our ability. In other words, pleasure is passive and dependent on external stimuli, while enjoyment comes from within but requires more effort to focus on our part. This also means that we can derive self-improvement from enjoyment, but not from pleasure. That being said, Csikszentmihalyi also emphasizes that “pleasure is also an important component on the quality of life, but by itself, it does not bring happiness” (p. 46). Between these two, enjoyment can bring us closer to the flow state.

So how do we achieve this flow state? In chapter 4, Csikszentmihalyi explained that there are two key dimensions involved: challenges and skill. For an activity to be a flow activity, it must provide a challenge that is slightly higher than our current skill. This will push us to a higher level of performance and provide a sense of achievement. When the level of challenges and skill is mismatched, however, it will often result in anxiety or boredom. It is best explained in the below diagram:

In this chapter, Csikszentmihalyi also mentions an interesting concept of autotelic personality (from the Greek αὐτοτελής or autotelēs. αὐτός or autos means “self” and τέλος or telos means “goal”.) People with this personality tend to find it easier to achieve flow as compared to others. The key trait of this personality is one that is also evident in survivors of extreme adversity, called “nonself-conscious individualism”, or a strongly directed purpose that is not self-seeking. Further definition:

People who have that quality are bent on doing their best in all circumstances, yet they are not concerned primarily with advancing their own interests. Because they are intrinsically motivated in their actions, they are not easily disturbed by external threats. With enough psychic energy free to observe and analyze their surroundings objectively, they have a better chance of discovering in them new opportunities for action. (p. 92)

Just like some of us are born with better muscle coordination or flexibility, some of us more predisposed to have this trait. Even so, I’d like to believe that this is a trait that we can develop and nurture in ourselves.

Csikszentmihalyi also found that several types of activities such as sports, games, or art can consistently produce flow. But since we can’t do only sports, games, or art all the time, it is crucial to be able to transform other types of activities that we do on a day-to-day basis to be a flow-inducing one. From chapter 5 to 8, Csikszentmihalyi discusses these activities: physical and/or sensory activities (e.g. listening to music, doing yoga) in chapter 5, symbolic skills activities (e.g. writing poetry, pursuing amateur scientific research) in chapter 6, work activities (yes, work!) in chapter 7, and social activities in chapter 8. There’s an interesting thing to note from chapter 7 in which he talks about the “paradox of work”. His studies reported that people have experienced more flow while on the job as compared to during leisure time, yet these same people are also wishing for more leisure time. There are several viable explanations, but the one highlighted in this book is that it is possible that people disregard their own flow experienced at work and instead referred to the cultural and/or societal norm that “work is not supposed to be enjoyable”; it is “supposed” to be a constraint to our free time.

In any case, what I gather from these chapters is that any activity, even the mundane ones, can be transformed into a flow-inducing activity by setting a goal before commencing the activity. For example, if we are going to listen to a song, we can set the goal as “I want to discern what are the musical instruments used in this song”. This goal will help us to focus and pay attention to the activity and learn to enjoy the present experience. The goal need not be grand or complicated, although it should not be a competitive goal either or the attention will be shifted to the competition instead. Approach the activity with a spirit of adventure and curiosity, with the goal to increase your level of skill!

The last two chapters talk about how to use flow to cope with stress or tragedies, and how to unify the experiences and the self-improvements gained from various flow activities to create meaning and cultivate a purpose in life. Csikszentmihalyi recommends reflection to support activity; before investing in a goal, it pays to stop and really questions whether if the goal is really something worth doing, attainable, and most importantly, something that you will enjoy (and get you in a flow state!).

Overall, I really like this book and would recommend it to anyone, especially those who are currently struggling and/or experiencing adversity in their life. It really helps to bring everything into perspective that “everything may not be as bad as it seems”, that perhaps it’s just our mindset, and there are steps that we can take to cope with it. What I have learned most from this book is that the key to happiness does indeed come from within; it’s all in the mindset and perspective that we use to look at our situation. It will take time and practice to attune them, but I believe it is definitely doable!

There are 240 pages on this book, not counting the notes and references. It shouldn’t take me too long to read, yet I found myself needing to stop a few times to absorb and reflect on the concepts and wisdom I learn from this book. It took me approximately 2 days to read this, so do allocate plenty of time if you plan to read this one for your summer reads!

Flow: The Psychology of Optimal Experience by Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi is located at Business Library or Humanities and Social Sciences Library, with call number BF575.H27C958