As part of psychology module The Last Dance, 38 students participated in a funeral simulation on 19 Sep.

As part of psychology module The Last Dance, 38 students participated in a funeral simulation on 19 Sep.

Thirty-eight bodies lay side-by-side and motionless on a cold, hard concrete floor, each covered with a white sheet. These rectangles of white were spread out across the foyer of the School of Humanities and Social Sciences building, a picture of calm and stillness.

Passers-by did a double take and stopped to silently observe the peculiar spectacle, while sombre music played in the background and eulogies were read aloud.

Amid the sea of white, boxes of colourful crayons were strewn on the ground and pairs of shoes were placed next to the bodies, waiting to be worn again. This was not a mass funeral in process.

The “dead” were students taking part in a 30-minute funeral simulation held on 19 Sep. Known as “I Died Today x NTU”, the event was a part of The Last Dance, a psychology module under the School of Social Sciences (SSS) that deals with death, dying and bereavement.

The module aims to encourage students to have conversations about death and mortality, which are often heavy, taboo topics in Singapore. Its funeral simulation, which was introduced last semester, aims to provide students with an immersive experience of death.

Breaking the stigma

“We do not talk about death enough due to its stigma in our culture,” said Dr Andy Ho, an assistant professor at SSS’ psychology department.

Dr Ho introduced the module in 2015 because he believed that it would ease students into the difficult topic and help them be more comfortable with discussing death openly.

If people do not think about or discuss death, they are often at a loss and do not know how to cope with their grief when a loved one dies, he said.

The 13-week course gives students a platform to discuss death through lectures, class presentations and experiential learning.

Although the module started three years ago, Dr Ho introduced the funeral simulation only last semester because he finally had a bigger team to assist him in carrying it out.

He introduced the “physical experience” to enhance his students’ understanding of the topic, he said.

“This immersive experience is good for students because normally in the classroom there is no spiritual and physical engagement. The simulation allows them to express what’s on their mind, and hopefully it will translate to a deeper level of learning,” Dr Ho added.

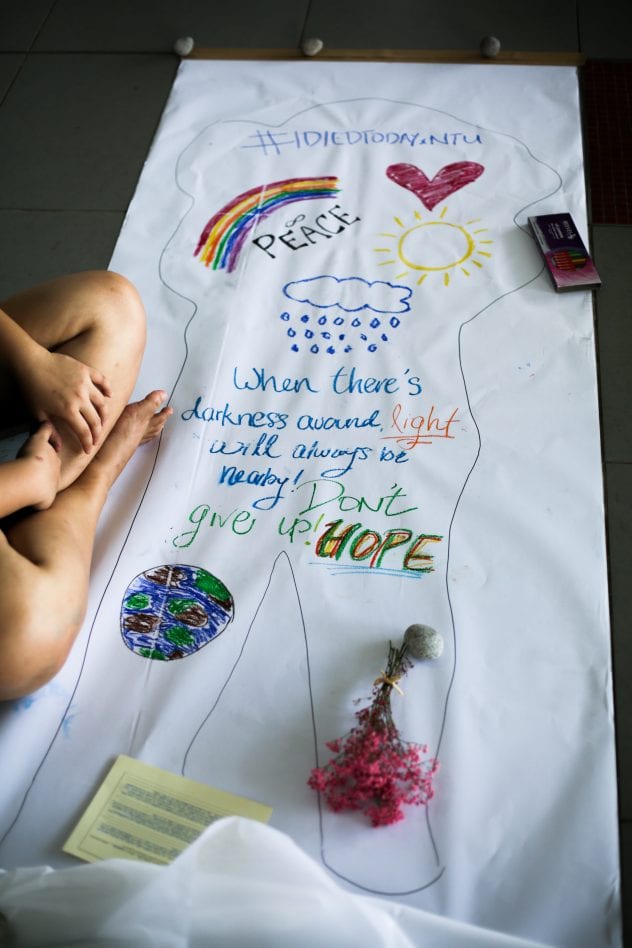

During the funeral simulation, students lay down on long sheets of canvas paper, which represented their graves, while teaching assistants traced outlines of their bodies.

The students were encouraged to imagine the thought process they would have if they knew death was rapidly approaching, and express their thoughts by drawing within the outlines.

Final-year SSS student Oh Jarrad Gjern, 24, took the opportunity to reflect on his life. His drawings were inspired by his loved ones because they were the people he would miss the most if he were to die, he said.

“I drew a group of people, who are close to me, where my heart is located on the canvas sheet. The purple flower at the centre of my drawing represents my girlfriend as she loves both flowers and the colour purple,” he added.

While some students reflected on happy moments in their lives, there were others who focused on sad ones.

Ng Jing Xi, 24, was one of them. When sketching on his canvas, the final-year SSS student thought about regrets and unresolved questions that he would have if he died.

His body outline was divided into three sections: an orange one where he drew flowers, a blue one where he drew a heart, and a red section where he scribbled the word “why” repeatedly.

The bold orange represented the bright side of life and the flowers were achievements he had “planted”. Meanwhile, the heart symbolised the loved ones he was leaving behind and the colour blue illustrated his sadness at having to do so, he said.

“This red part represents frustrations, stemming from many questions like ‘Why am I leaving the world so early?’ and ‘Why did I have so little time to do what I wanted to?’ ” Ng added.

“I want to remove as many ‘whys’ as possible but I’m sure there will always be regrets left behind,” he added.

A cathartic experience

Despite the morbid topic, students like Oh found the experience to be enlightening.

Although the idea of simulating death was slightly uncomfortable, he was excited to participate in the funeral simulation and approached it with an open mind, Oh said.

“During the simulation, I realised that my death would not cause much disturbance to the world. This was comforting as I felt at ease knowing that my death would not burden others,” he added.

Besides the funeral simulation, students discuss issues such as palliative care and government policies related to death during the module’s lectures and class presentations. They also learn how to manage attitudes towards death.

These discussions have helped students such as S. Priyalatha, 23, change their mindset about death.

She is now able to have open discussions about death with her family, while tackling the topic with sensitivity, the final-year SSS student said.

“Conversations about death don’t always have to be sad. When you know what your family members want for their funeral rites and how you are going to be sent off, everyone will have proper closure,” she said.

The class has also helped her come to terms with the deaths of children whom she interacted with when she interned at the Children’s Cancer Foundation.

“It really affected me but this module opened my eyes to the topic of death, and how it happens to young children too. We always celebrate birth, but we often overlook death although it might happen at any time,” she added.

The module also allows students to reflect on their priorities and find their purpose in life, said Dr Ho.

Since death happens to everyone, we should all be prepared to deal with it, he added.

“If we want to drive a car, we can take driving lessons. If we want to fly a plane, we can take flying lessons. But we all die in the end, so why is there no one to help us deal with these emotions?”

As part of psychology module The Last Dance, 38 students participated in a funeral simulation on 19 Sep.

As part of psychology module The Last Dance, 38 students participated in a funeral simulation on 19 Sep.